Albany’s Tax-the-Rich Deal Sends Wealthy to Washington Looking for Relief

Deals to raise taxes on New York’s millionaires and companies could send both fleeing the state, business leaders and fiscal experts warn — unless Washington steps in and restores some old deductions.

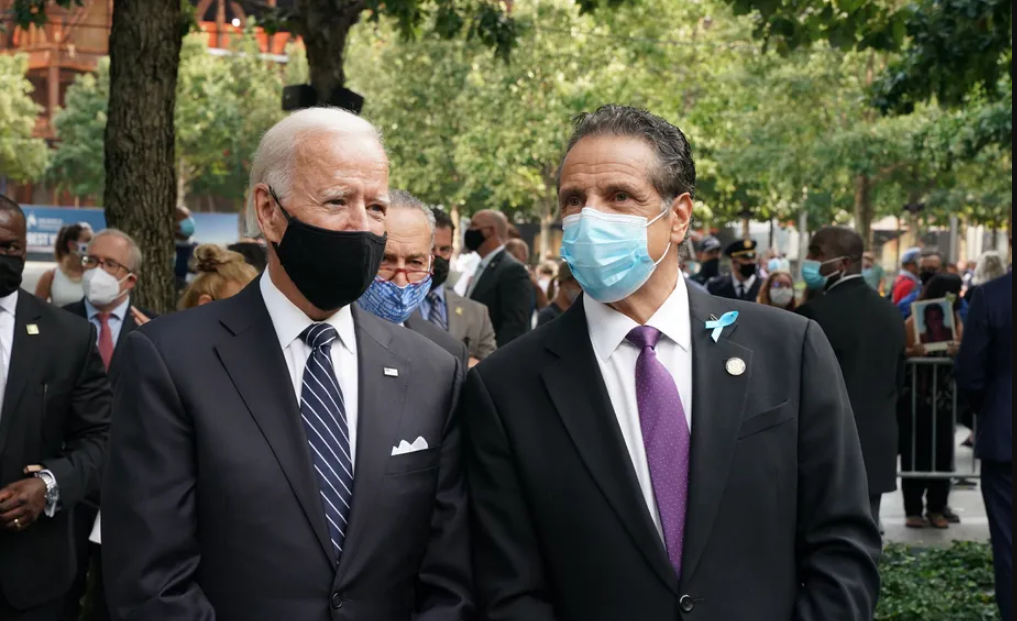

Even as legislative leaders and Gov. Andrew Cuomo had yet to officially seal an agreement on New York’s second straight pandemic budget, all indicators pointed to the state levying the country’s biggest income tax on the wealthy.

The $4 billion-plus income tax increase would mark at least a partial victory for progressive Democrats, who argued that well-heeled New Yorkers and companies that prospered during the pandemic should foot a bigger share of the tab for increased spending to help those staggered by the crisis.

On the losing side were business interests and Cuomo, who argued for a modest tax boost amid concerns that an exodus of well-to-do New Yorkers and top-flight firms could stall the state’s recovery and blow new holes into the social safety net. The governor’s lack of influence on the budget was evident in a news conference Monday when he avoided mention of the tax increases.

Cuomo and others also cited historic pandemic aid from Washington — where the wealthy are turning their attention in a bid to claw back state and local tax deductions known as SALT.

“The question on the federal side is whether the SALT deduction will come back, which could balance out some of the increase,” said Alan Goldenberg, state and local tax principal at the accounting firm Anchin Block & Anchin.

A State Record

The governor and legislative leaders appeared Monday to have reached a deal that will raise the income tax rate on individuals making more than $1 million and couples generating $2 million a year to 9.65% from 8.82%.

Even bigger hikes are in store for the super-rich, with a 10.3% levy for people making more than $5 million a year and 10.9% for those with incomes over $25 million.

For millionaires who live in New York City, believed to be the vast majority in the state, the combined state and local income tax burden would range from 13.5% to 14.8% — become the highest in the country. California levies a 13.3% rate on taxpayers making more than $2 million.

The rates, which are temporary, are lower than those proposed by the state Senate and Assembly, and many other ideas for new taxes were not included in the budget.

Still, they will raise about $4.3 billion a year and are a clear sign of Cuomo’s waning clout amid dual investigations into sexual harassment allegations and his handling of COVID-19 deaths in nursing homes.

Cuomo had proposed only a little more than $1 billion in higher taxes on millionaires — and said they would be needed only if federal aid was inadequate. Federal aid is expected to total more than $30 billion, far more than the governor had said was necessary.

“This budget advanced a political agenda but sets back economic recovery,” said Kathryn Wylde, president of the Partnership for New York City, who had sought to marshal opposition to new taxes. “The spending advocates very cleverly called for $50 billion in new taxes and many legislators convinced themselves that agreeing to ‘only’ $5 billion a year in tax increases is somehow a break.”

Others noted that the state budget, expected to top $200 billion when all the details are disclosed, represents a substantial increase in state spending over the $178 billion authorized last year as the pandemic’s deadliest days neared.

“This budget is true to the state’s motto ‘Excelsior,’ whether it would be tax rates or spending, increases in both appear to be substantial,” added Andrew Rein president of the Citizens Budget Commission.

New York state and local government spending outpaces that of every state but Alaska, according to an analysis for THE CITY by the Volcker Alliance State Budget Team, a research group that tracks fiscal policy issues across the country. Per capita spending in 2018 totaled $18,789.

Sen. Michael Gianaris (D-Queens), a leader in the fight for higher taxes, wouldn’t comment on the budget or its impact until after final approval, said a spokesperson. Other legislative leaders also remained mum, though tax supporters have contended that threats by the wealthy and firms to leave New York are empty, even as the pandemic has made remote working part of the corporate culture.

Price Hikes Seen

Whether state and local tax deductions, which were capped at $10,000 in the 2017 Republican tax bill, can be restored remains uncertain.

Seven Democratic governors, including Cuomo, wrote President Joe Biden recently urging him to support repeal of the cap. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) earlier this year introduced legislation to do just that, and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi also favors the move.

However, SALT repeal would cost the federal government about $90 billion a year. The White House said those who wanted to reinstate the deduction would have to find a way to pay for it.

While Washington could lessen the impact of the millionaire’s tax hike, it can’t cushion the increase in the corporate franchise tax to 7.25% from 6.5% for all but small firms. With few details available, it isn’t yet clear what size businesses will be exempted.

The state corporate tax rate remains in line with those in other states in the region. But New York City and the MTA impose their own franchise taxes that pushes the rate past 15%, a third higher than any other state. Almost no local government imposes such a tax, notes Jared Walczak, an expert on state taxes at the Tax Foundation.

Because of the way New York computes corporate taxes on the basis of sales, the impact of this increase won’t be clear for several years, CBC’s Rein notes, but will make everything purchased in the state more expensive.

‘Breaking Point’ for Some

Business leaders did find a few bright spots in the budget. No new real estate taxes were imposed, a key objective of the Real Estate Board of New York as tenants and landlords alike suffer amid the pandemic-wrought economic crisis.

In addition, a special 1% capital gains tax and increases in the estate tax fell by the wayside.

Nevertheless, they are worried about the long-term impact on the state’s level of spending and competitiveness.

“The real issue here is that once you raise these dollars and pump them into the budget and start spending them, it will be hard to take them out,” said Stephen Berger, an investment banker who has been advising governors since Hugh Carey. “They are building a spending base that increases dramatically and they will not pull it back.”

This is especially true in K-12 education, which will receive a more than $10 billion in aid boost from the $1.9 trillion Biden federal aid legislation and reportedly added state money as well.

While much of it is needed to prepare schools to reopen and to make up for the educational losses during the pandemic, some of the funding continues the policy of subsidizing wealthy districts that can pay for local schools on their own, Rein noted.

The key will be whether a federal income tax increase planned by the Biden administration increases the overall burden of the wealthy, whether Congress restores the state and local deduction and whether taxpayers believe the increase is really temporary.

The previous state millionaires tax increase, first approved in 2009 following the financial crisis, was also billed as a stopgap but has been extended four times.

“When people start looking at their overall tax and financial situation, some people will say it may not be worthwhile to relocate if the increase is temporary or if I can get some of it back on my federal return,” said Goldenberg of Anchin. “But there is a breaking point people reach when it comes to taxes. And because of the pandemic people have been away from New York and have the flexibility not to come back.”

This article was originally posted on Albany’s Tax-the-Rich Deal Sends Wealthy to Washington Looking for Relief