Black Lives Matter meets Yellowstone

MAMMOTH HOT SPRINGS, Wyo. — Richard Franklin put his family vacation on hold for a few hours Saturday morning.

Franklin, a Black man traveling with his family from Atlanta to Yellowstone National Park for the first time, parked near the visitor center in Mammoth Hot Springs and walked with one of his daughters toward a group of 20 or so Black Lives Matter protesters.

“Mind if we join you?” Franklin asked.

The all-white group of protesters quickly agreed that Franklin’s family was more than welcome.

“Do you have a mask you can put on?” asked Maddy Jackson, the protest’s organizer.

“Sure,” Franklin said. He pulled a purple bandana out of his shorts pocket and wrapped it around his face. Jackson gave him a name tag, and he picked up a sign and stood chatting with Jackson, maintaining social distance.

Community members of Mammoth Hot Springs and Gardiner organized the protest, joining millions of people across the United States who have participated in Black Lives Matter protests and rallies in response to the police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other Black people in recent months.

Masks, name tags and social distancing were requirements for protesters in Yellowstone’s so-called free speech zone, just outside the Horace Albright Visitor Center at park headquarters. The protest was limited to 30 people, and protesters were not allowed to raise their voices or mount signs on wooden sticks, per National Park Service regulations. The conversation among protesters mainly consisted of friends catching up on their lives during the pandemic.

Reaction from the steady stream of cars that drove by during the four-hour event was overwhelmingly supportive. Many people honked their support, and quite a few stopped to take pictures. A few jeered, “get a job,” or “all lives matter.” A pickup drove by flying a “Blue Lives Matter” flag. Another flew a “Black Lives Matter” flag.

Mary Beth Reagan, who lives in Mammoth and attended the protest, said the gathering was unique in that it both recognized the local community and reached well beyond it, to visitors from across the United States.

“Maybe it’ll start a conversation,” Reagan said.

Reagan, a mother of two who took her young sons to the protest, said it meant a lot to see a demonstration where members of a majority-white community came together in support of Black lives. Throughout the event, several people of color, including Franklin and his family, temporarily joined in, and Reagan said she was glad her sons could partake of an experience that’s unusual in the daily life of Mammoth.

“That’s why I brought my kids. We don’t get to experience a lot of diversity here,” she said.

Franklin, too, said he was glad to see so many white people supporting the movement.

“God is shining on us today,” he said.

Saturday’s protest took place as conservationists nationwide are reckoning with the environmental movement’s own history of racism. Last week, the Sierra Club announced it is reexamining the history of John Muir, who helped start the organization and played an instrumental role in the conservation movement in the U.S. Muir also perpetuated white supremacy, according to the Sierra Club, and made discriminatory comments about Black and Native people.

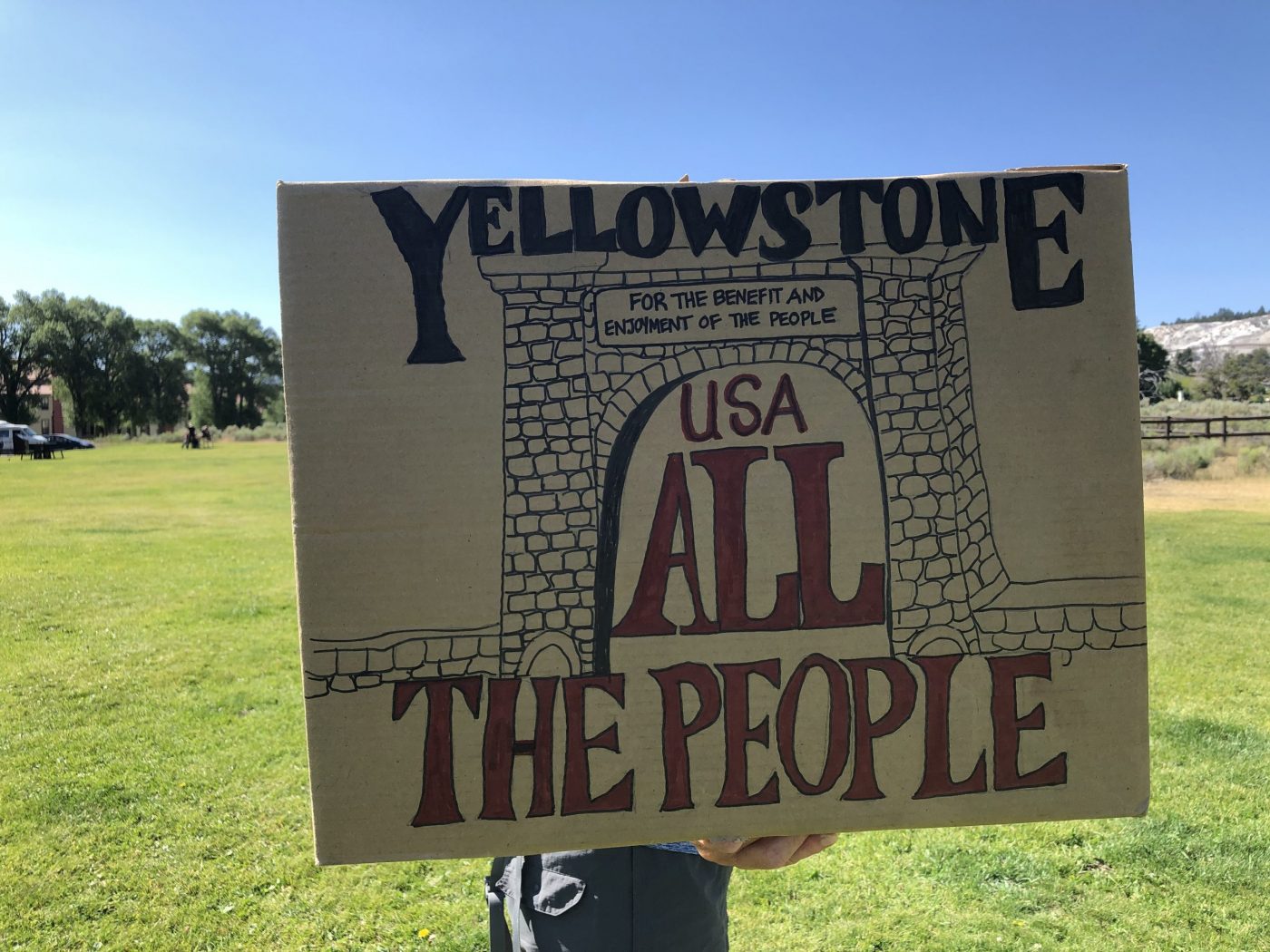

The Roosevelt Arch near Gardiner, whose cornerstone was laid in 1903 by President Theodore Roosevelt, proclaims that Yellowstone is “For the benefit and enjoyment of the people.”

Carrie Holder, who has lived in Mammoth Hot Springs for 32 years, made a sign emphasizing that Yellowstone should be for “all the people.” Holder said that means everyone: people who live in Gardiner and Mammoth, the millions of people who visit the park each year, and people who don’t visit the park, but support the existence of a place where grizzly bears, bison and wolves can roam free.

The arch hasn’t always symbolized that inclusiveness. A picture from 1926 provided to Montana Free Press by park historian Leslie Quinn shows the Livingston Ku Klux Klan gathered in their robes in front of the arch on an outing to Yellowstone.

Wallace Stegner called national parks America’s “best idea,” describing them as “Absolutely American, absolutely democratic, they reflect us at our best rather than our worst.”

But that hasn’t always been true in Yellowstone.

Ashea Mills, a park guide who lives in Gardiner and joined the protest, said Yellowstone’s history has been whitewashed. Throughout the park’s history, the idea that Native people didn’t really use the Yellowstone area has been promoted, despite a long history of Native people living there.

“Our interpretation of Yellowstone is sorely misguided,” Mills said.

The park, like every other park in the National Park system, is on land that was once occupied by Native Americans. There is evidence of Native people in Yellowstone going back 11,000 years, and a number of tribes lived in the region at least seasonally into the 19th century. The Sheepeater people lived in Yellowstone until it was established as the world’s first national park in 1872. Some Sheepeater descendents still live on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming. When the Nez Perce people sought refuge in Yellowstone in 1877, they were chased out by the U.S. Army.

Yellowstone was the last refuge for wild bison, which were driven nearly to extinction by a military campaign to control Native Americans. In 1902, the last 23 wild bison were located in Pelican Valley, one of the park’s most remote areas. The species was later recovered in Yellowstone’s Lamar Valley. Today, about 4,000 bison live in Yellowstone.

Yellowstone still promotes the memory of racist American namesakes, despite pleas from Native Americans to change place names including Hayden Valley, named after Dr. Ferdinand V. Hayden, who advocated the extermination of Native peoples, and Mount Doane, named for Lieutenant Gustavus Cheyney Doane, who oversaw the Marias Massacre that killed 173 Blackfeet people in 1870.

The idea of national parks and wilderness today is largely conceptualized around the absence of people, but people live in and around Yellowstone, Holder noted.

The town of Mammoth, in Wyoming, is five miles south of Gardiner, in Montana. While Mammoth residents have to drive to Cody to renew their driver’s licenses or get new license plates, the community is more closely affiliated with Gardiner, the only park entrance that is open year-round. Children in Mammoth attend school in Gardiner, and the two towns share one community Facebook group. Gardiner had 875 people in the 2010 census. Mammoth had 263. As of the 2010 census, Gardiner is 97.3% white. Nearly everyone who lives in Mammoth works for or has a household member who works for the National Park or one of its concessionaires.

Many of Saturday’s protesters declined to say where they work, saying that doing so could suggest a violation of the Hatch Act, a law designed to prevent federal government employees from using their positions to influence political activity.

As it has in many rural communities, the protest planning generated significant pushback on Facebook, Jackson said. Some comments about the protest encouraged grizzly bears to eat protesters. A local outfitter posted that he’d heard the protesters were “terrorists” who planned to paint the Roosevelt Arch black, and said he and other locals would guard and protect local businesses. Park County Sheriff Brad Bichler replied to the outfitters status with the comment, “Thank you my friend for always speaking your mind and the truth.”

As a result of the online backlash, and after a recent fire in Gardiner that burned three prominent local businesses, Jackson said she didn’t want to create any additional consternation in the community, and so decided to move the protest from its initial location at the Roosevelt arch to Mammoth. More than one Black Lives Matter protest attendee said the presence of park law enforcement at the new location made them feel safer.

Holder said it was the first civil rights protest in the community she can remember.

Jackson said that while the populations of Mammoth and Gardiner aren’t especially diverse, she wants to create space for people who might want to move there. In recent years, housing prices in Gardiner have skyrocketed. As a result, many community members have been priced out of the home-buying market, and school enrollment has declined.

Jackson said she thought it was important to demonstrate that there are open-minded people in Gardiner and Mammoth. The community brings in workers each year from across the country and around the world. At the local grocery store, each clerk features their home state or country on their name tag.

Brought to you by our members

Our independent reporting is funded in part by more than 1,000 members who care about high-quality Montana journalism.

Visitors to the national parks are overwhelmingly white, according to ABC News. Non-white people make up 42% percent of the national population, but just 23% of park visitors.

Park employees are also overwhelmingly white. More than 83% of National Park Service employees across the agency’s more than 400 properties are white — about 20% higher than the rest of the federal government, according to E&E News. Jackson said she recognizes the challenges posed by having a majority-white staff welcoming people of color to the park.

Franklin, the Black man visiting from Atlanta, didn’t stick around for the full protest. A little while into the demonstration, his wife and other daughter joined, and just before he and his family left, he asked the other protesters to gather around. He explained that he felt heartened to see so many white people supporting the cause, especially in a rural place. He asked the protesters to stick with it. He said it meant a lot to him, and to other people of color who drove by, honking their support.

And then he apologized to the group for having to leave.

“Sorry I’ve got to go,” Franklin said. “I mean, I am on vacation.”

The article was published at Black Lives Matter meets Yellowstone