One Indianapolis district’s bilingual classrooms attempt to address learning gaps for Hispanic students

A group of first and second graders sat cross-legged on a rug, sounding out words on the flash cards their teacher was presenting at the front of the classroom.

“En-ton-ces,” they pronounced in unison. “Bi-en.”

Unlike the other students in the school that day who spoke, read, and wrote in English, this group was working on their Spanish reading skills. They were attending the last day of a dual-language summer school program in Lawrence Township, one component of the robust Spanish-language support system the district has implemented to serve a growing Hispanic population.

Since the 2010-11 school year, Hispanic enrollment at Lawrence has more than doubled, part of an uptick in Hispanic residents across the country that has resulted in a boom of Indianapolis Hispanic students. Across the city’s 11 school districts, Hispanic enrollment has shot up nearly 59% in the past decade, and now more than 20% of all students are Hispanic.

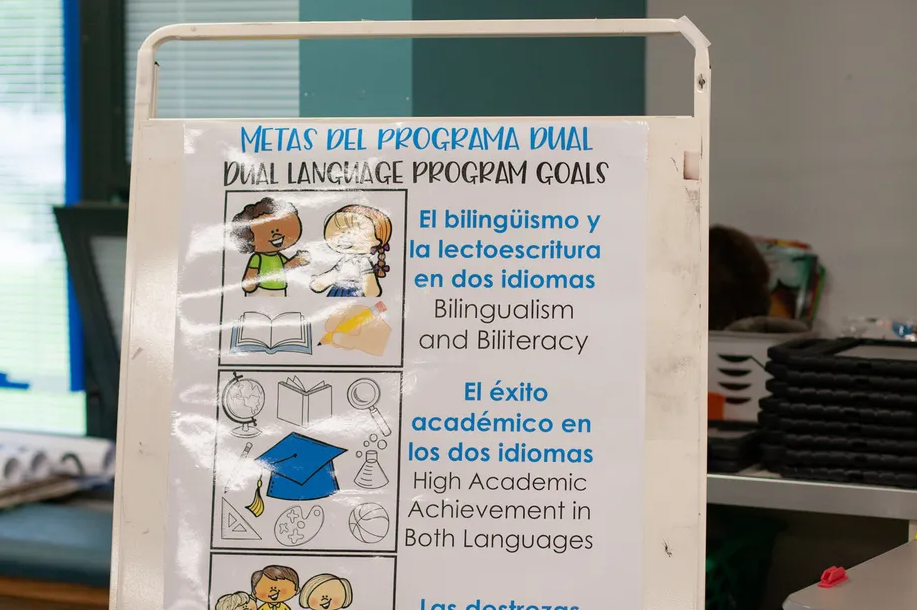

To support this community, Lawrence Township has gone all in on dual language, which relies on the theory that teaching young students primarily in their first language will help them learn English more quickly. The district has added dual-language programs to seven schools, including Harrison Hill, in the past five years.

“This is an amazing school,” said Sonia Torres, a Harrison Hill parent whose kids are enrolled in the dual-language program. “They help my daughter a lot.”

Lawrence is an outlier among Indianapolis districts, most of which offer little or no dual-language instruction, instead relying on traditional methods of English immersion and pulling students out of class for English tutoring. But while each school has its own approach to teaching Spanish speakers, they share one thing in common: severe academic gaps for Hispanic students and English learners.

Just 7.4% of Lawrence English learners in grades 3-8 passed the English and math portions of the ILEARN exam in 2019, compared with 31% of non-English learners. Racial gaps are also apparent — Hispanic students trailed their white classmates by 35 percentage points on the tests.

As Indianapolis’ Hispanic population growth shows little sign of slowing, schools face an important question: How should they adjust curriculum and culture to best serve all students and to address learning gaps?

The case for bilingual instruction

Patricia Gándara, an education professor at UCLA, said new research in the past five years has decisively found bilingual education to be more effective than traditional English immersion for teaching English.

“It is just so beneficial in so many ways,” Gándara said. “It just sends a really strong message that what you know in your native language is important.”

Gándara said two-way dual-language programs, which place native English speakers and English learners in the same classroom where they all learn both languages, have been found to be the most effective. Bilingual programs that teach students in their native language first, slowly phasing in English as they age, are also more effective than English immersion, she said.

She said it would be a mistake for schools not to provide as much dual-language programming as they can.

In light of this research, Lawrence Township launched additional dual-language programs for English learners at six elementary schools five years ago, and added a second two-way program the next year.

The district already had a popular two-way dual-language immersion program at Forest Glen Elementary. The new schools would only enroll Spanish speakers, providing Spanish-speaking teachers to instruct them primarily in their first language for the first few years. The district started with kindergarten and first grade classes, then added one grade level per year.

About 15% of Lawrence’s English learners, most of whom are Hispanic, are enrolled in dual-language classrooms, according to the district. The programs established in 2016 have just started to add fifth graders, and as students progress, they are outperforming their peers in English immersion on the ILEARN and other benchmark tests, said Chief Academic Officer Troy Knoderer.

“For us, that means we need to continue growing our dual-language program, because we’re seeing better results,” Knoderer said.

Eventually, he said the district hopes to offer dual language to all English learners. This is the district’s primary strategy for addressing its pervasive academic gaps for English learners.

But because of the difficulty in hiring bilingual staff, it could take a while to fully expand the program.

Obstacles for bilingual classrooms

To teach Spanish-speaking students in their native language, you need teachers who can speak Spanish. In Indiana, qualified bilingual teachers are rare.

As the state faces a critical teacher shortage, most school districts have had trouble filling job openings. Add on the additional resume requirement of bilingualism, and finding qualified candidates becomes even harder.

Erika Tran, language program coordinator at Lawrence, said it’s difficult to attract dual-language teachers to Indiana, especially because more than a dozen programs across the state compete for the same tiny pool of candidates.

Tran said the district prefers to hire Hispanic teachers, both because teachers in the bilingual program need a strong grasp of Spanish, and because the district wants the ethnicity of the teachers to reflect the identities of students.

She said the district has gone so far as to recruit educators directly from Spain and Puerto Rico through state-sponsored programs. None of the district’s dual-language teachers are from Indiana, which has a particular lack of Hispanic educators.

Because of these challenges and others, even administrators who believe bilingual education would benefit students may hesitate to start dual-language programs.

Wayne Township Schools have seen a 77% increase in Hispanic enrollment since 2011. To serve this growing group of Spanish-speaking students, the district has doubled down on traditional English immersion.

As in Lawrence, Wayne English learners have very low ILEARN scores — just 10% were proficient on the English and math sections in 2019. The students aren’t as far behind their non-English learning counterparts, who scored significantly worse than Lawrence’s — only 26% passed both tests.

Denita Harris, former English learner curriculum coordinator at Wayne Township Schools, said she knows bilingual education is more beneficial for students than the district’s current model. But even so, bilingual programs at Wayne are not going to happen anytime soon for financial reasons.

“You have to think about, how is this sustainable?” Harris said. “You can start something, and it fizzles out in a year or two. The reality is, when we do something, we want to do it well.”

Harris said while the state department of education offers some grants to support dual-language programs, the money is short term. To launch a quality program, Wayne would have to commit to finding enough teachers to eventually build a K-12 program, she said. The enormity of these changes has discouraged administrators from pursuing dual-language instruction.

Gándara, the UCLA professor, acknowledged that bilingual education isn’t a priority for many schools.

“We could certainly produce the teachers that we need — if we were serious about it,” she said.

She said schools and universities need to tap into pools of bilingual students and encourage them to pursue teaching. In addition, she said schools should offer bilingual students stipends to incentivize them to take jobs.

“It’s a bigger job than the regular teaching classroom,” she said. “We need to honor the fact that they bring special skills.”

Will dual language close academic gaps?

Indianapolis schools’ test scores show pervasive academic gaps for English learners and Hispanic students. But Gándara said these scores offer a narrow view of success for language programs.

She said to accurately measure English learners’ grasp of content, especially before third or fourth grade, standardized tests should assess them in their native language. Because the existing tests all measure English proficiency, they prevent students from showing what they actually know.

“When you put kids in an English-only environment, nobody tests them to see what they actually know,” Gándara said. “The assumption is that they’re blank slates, we have to start from zero, because you don’t speak English. But these children know a lot of things.”

Gándara added that English learners are first and foremost children of immigrants. In addition to their lack of English fluency, they are more likely to be low-income, their parents are less likely to know how the U.S. education system works, and especially in the pandemic, they were less likely to have parents working from home and assisting with virtual learning — all factors contributing to lower test scores.

Rather than focusing on composite standardized test scores, Gándara suggested other measures, like testing younger bilingual students in their first language and monitoring whether students’ English test scores improve over time.

Regardless of test scores, Sonia Torres, the Harrison Hill parent, said she loves how Lawrence’s dual-language program has helped her fourth grade daughter learn English while maintaining Spanish fluency. Her son is going into first grade this year, and will also enter a bilingual classroom.

“I feel like they’re going to have a better future,” Torres said. “They’re going to do a great job.”

This article was originally posted on One Indianapolis district’s bilingual classrooms attempt to address learning gaps for Hispanic students