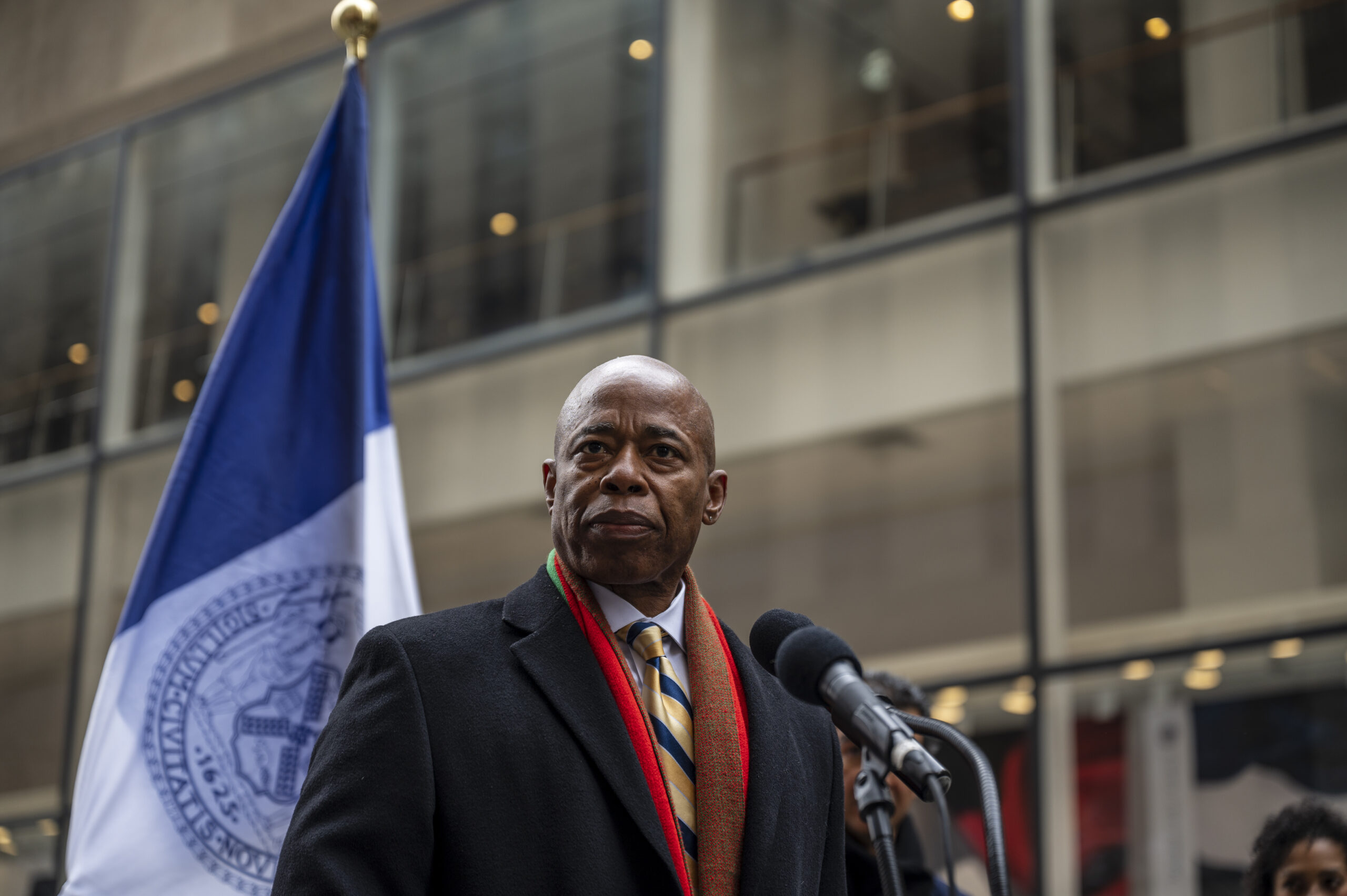

What Will Eric Adams Do for Beleaguered Businesses? Owners Air Hopes While Awaiting Answers

In September, Eric Adams made a pledge to the city’s business people they had been waiting eight years to hear.

“New York will no longer be anti-business,” Adams, then the Democratic nominee for mayor, pledged at an annual gathering of finance, tech and policy experts in Manhattan. “This is going to be a place where we welcome business and not turn into the dysfunctional city that we have been for so many years.”

Since then, Adams has provided virtually no specifics on what he will do differently than Bill de Blasio to revive the city’s deeply wounded economy. So business leaders and experts on the economy have come up with their own measures by which they will decide whether the new mayor’s statements were just rhetoric — or will manifest in policies that represent a fundamental change in City Hall’s attitude toward them.

Restaurants want him to immediately reauthorize propane heaters for outdoor dining. Development experts want him to build on de Blasio’s success in his last two months rezoning Gowanus and SoHo, by launching similar efforts in other neighborhoods.

Many call for a greatly expanded and overhauled workforce strategy, including help for the hundreds of thousands of workers whose jobs are unlikely to return post-COVID and a proposed new $100 million retraining fund for those who’ve lost their jobs.

Everyone clamors for a mayor who will finally deliver on promises to make dealing with city government easier, especially for small businesses. Underlying almost all the items on the wish list is a broader plea for competence.

“The single most important thing the Adams administration can do is to restore the notion that New York can be governed again,” said James Whelan, president of the influential Real Estate Board of New York. “Show that one can reduce crime in a fair and just way and that you are committed to a good quality of life for folks throughout the five boroughs.”

Winning over the business community and restoring their confidence in New York’s prospects is crucial for Adams given the fragile state of the economy. The city remains 345,000 jobs below its pre-pandemic peak, or almost 10%. The nation is only a little more than 2% below the early-2020 record. The city’s unemployment rate of 9% is almost double the nation’s.

Battling Bureaucracy

Aides to the new mayor have declined repeated requests from THE CITY to discuss his pro-business plans.

But Adams’ own first act as mayor signaled no rush to break from de Blasio’s policies when it comes to pandemic measures with an impact on businesses. Not long before his inauguration, Adams announced he will continue COVID vaccine mandates for venues and employers — including new requirements that children show proof of vaccination before entering.

The decision rankled some business owners, who say the policies are taking a toll.

“Kids can’t come in unless they are fully vaccinated, and that has become a big issue especially for families and tourists,” said Jeff Garcia, owner of Monamour Coffee and Wine with locations uptown and in The Bronx. He said his business has declined more than 30% since the omicron variant began sweeping the city last month.

Owners of restaurants, cafes and bars are meanwhile waiting for Adams to act on his promise to move quickly to again allow propane heaters to be used to hear outdoor spaces — equipment de Blasio approved early in the pandemic but revoked under pressure from the fire department.

“That would send a signal to the industry that he’s actually going to enact policies in his first days that would help the industry,” said Andrew Rigie, executive director of the NYC Hospitality Alliance.

Virtually every one of the more than 20 business people interviewed for this story said that the mayor will be judged on whether he makes doing business with the city easier.

“The biggest problem facing small business is navigating the bureaucracy,” said Tony Dyer, one of the owners of Levante Italian restaurant in Long Island City, who is trying to open a second eatery in the neighborhood.

He noted that most landlords give a period of free rent to allow a build out of a dining space, but “you never finish within that time. Just to get a response from the Department of Buildings can take months.”

Workforce Ambitions

Adams has already sent one signal about his priorities, in retitling a key deputy mayor position. What was the deputy mayor for economic development and housing is now the deputy mayor for economic and workforce development, a position held by Maria Torres-Springer.

Torres-Spinger, who most recently served as an executive at the Ford Foundation, is a veteran of both the Bloomberg and de Blasio administrations who has run agencies key to the economy: Housing Preservation and Development, the Economic Development Corporation and the Department of Small Business Services.

“She cares about equity and recognizes the major engines that drive the city’s economy,” said Carl Weisbrod, who worked with her while running the Department of City Planning during de Blasio’s first term.

The change comes amid massive dislocation of workers in the pandemic, especially in leisure and hospitality. Economist James Parrott of the New School estimates as many as 200,000 jobs that existed before COVID may never return, and those workers will need to be retrained.

Workforce development advocates call for spending at least $100 million on programs that economically support people who lose their jobs and retrain for growing and better paying industries such as tech, health care and life sciences.

They note that as many as 21 city agencies are involved in workforce issues with little coordination.

“We need a massive reemployment strategy that integrates training and earnings,” argued Jose Ortiz Jr., executive director of the New York City Employment and Training Coalition.

Developing Relationships

Building more housing, including a substantial number of affordable units, is also high on the business agenda.

With the number of manufacturing workers in the city likely to fall below 50,000 this year, or only about 1% of all jobs, real estate interests want Adams to rezone areas where development is hobbled by restrictions preventing housing and other commercial uses.

Long Island City, Bushwick, the areas north of Madison Square Park in Manhattan and undeveloped areas along the waterfront are areas where the Department of City Planning has already done substantial preliminary work, said real estate lawyer Mitch Korbey of Herrick Feinstein.

A key priority for the real estate industry will be convincing the state legislature to extend the 421-a tax break, which provides steep reduction in property taxes on new rental buildings and expires in June.

A major fight is expected, since 421-a resulted in the city forgoing $1.7 billion in the year ending June 30, according to the city’s annual comprehensive financial report.

Adams received strong campaign fundraising support from the real estate sector and has so far sustained hopes he’ll be an ally.

Robert Morgenstern, who owns and manages 2,000 apartments in the city, attended an early fundraiser for Adams and quickly became a contributor.

“I expect the city will become safer. I suspect the police will be more respected and something will happen with the homeless problem,” he said.

This article was originally posted on What Will Eric Adams Do for Beleaguered Businesses? Owners Air Hopes While Awaiting Answers