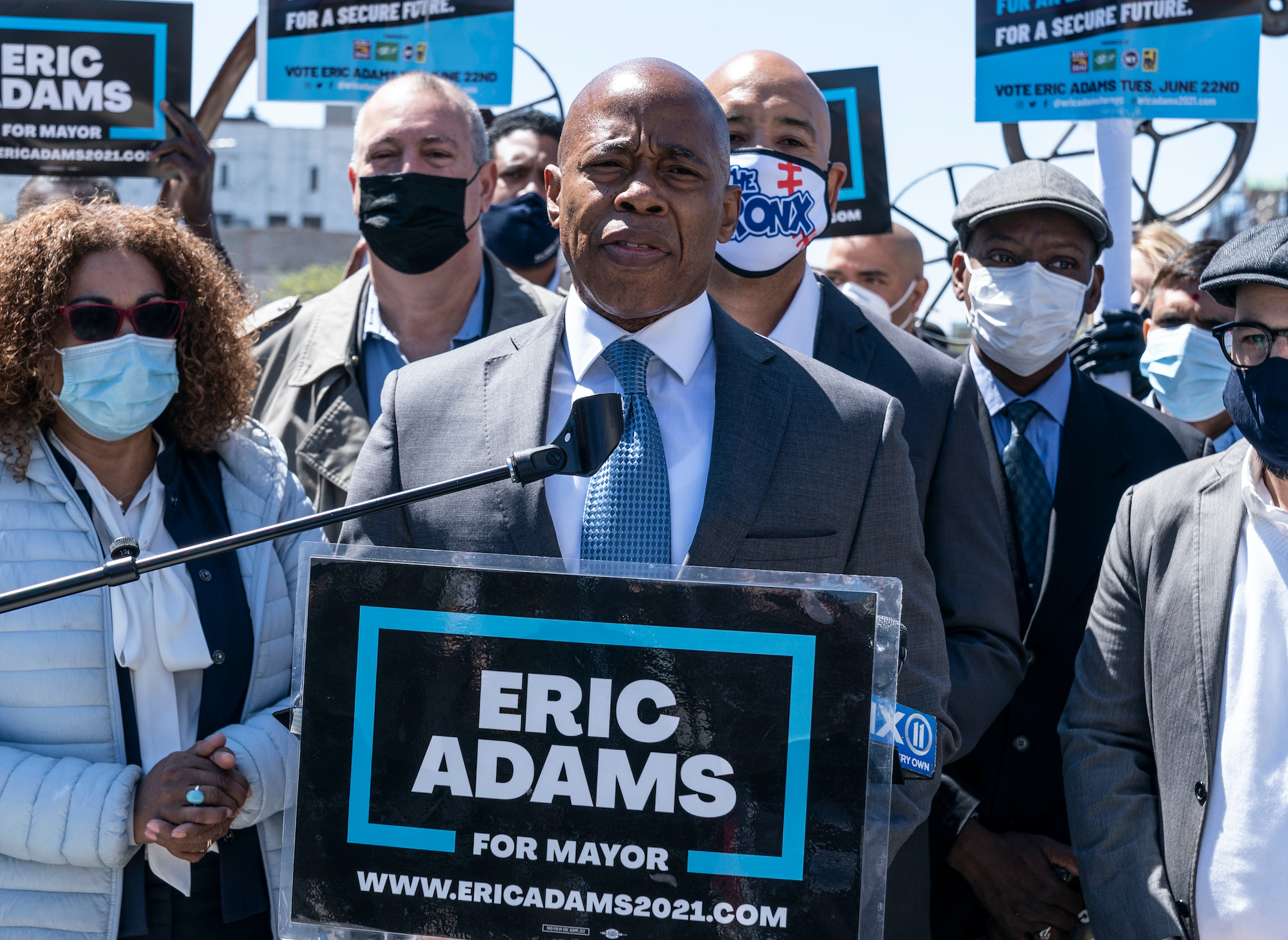

Eric Adams’ Aqueduct Casino Bid Scandal Interview Transcript Reveals Contradictions and Shaky Memory

The now-mayoral candidate repeatedly told investigators he couldn’t remember key details of his birthday bash at a fancy Manhattan club, documents show. Among the guests: bidders for a “racino” contract who donated thousands to his campaign.

The political fundraiser took place on a Thursday night just ahead of the 2009 Labor Day weekend inside Manhattan’s Grand Havana Room, an exclusive private club high above Fifth Avenue.

The star of the event: then-state Sen. Eric Adams of Brooklyn.

Inside the polished mahogany confines of the elite venue, a powerful mix of elected officials, lobbyists and their clients mingled — including two bidders seeking to run a casino at Queens’ Aqueduct Racetrack, a project Adams was involved in vetting.

It was a fundraiser, but it was also Adams’ birthday party: He’d turned 49 just two days before.

At one point during the celebration, Adams publicly thanked one of the Aqueduct bidders, according to a lobbyist who was there. Later, the lobbyist and his client — one of the bidders — wrote $11,500 in checks for Adams’ re-election campaign.

Adams’ campaign pulled in about $38,000 — just another typical fundraiser for an Albany politician. A few months later, however, it became something less ordinary: a subject of inquiry in a corruption investigation led by the state inspector general.

During a May 2010 deposition, lawyers working for then-IG Joseph Fisch grilled Adams under oath about the Havana Room fundraiser and his involvement in what they would ultimately determine was the ethically questionable selection of the bidder that attended the event and then wrote checks to Adams.

At the time of the event, Adams chaired the state Senate’s Racing and Wagering Committee, which was involved in the selection process for the “racino” operator.

When the IG’s lawyers brought up the Havana Room affair, Adams said he could not recall whether any of the Aqueduct bidders had shown up or whether any had contributed to his campaign.

“I’m not sure who was there,” he responded. “It’s possible, but I’m not sure.”

Transcripts of that session obtained by THE CITY, via a public records request, reveal that Adams repeatedly said he could not recall many of the details regarding his interactions with the partners of and lobbyists for Aqueduct Entertainment Group (AEG).

That’s the bidder ultimately picked by the Senate and Assembly leadership and approved by then-Gov. David Paterson.

And throughout the examination, Adams made statements contradicted by emails and other records the inspector general collected as part of his investigation.

Inside Info Leaked

In the IG’s October 2010 final report, Fisch charged that the state Senate leadership had leaked insider information from competitors to AEG, a politically wired group that included a Las Vegas casino operator and a local developer.

The behind-the-scenes backing of AEG took place in the summer of 2009 when Republicans briefly regained and then lost control of the Senate after two insurgent Democrats briefly aligned themselves with the GOP.

By July of that year, as the Aqueduct selection process inched forward, then-Senate Majority Leader Malcolm Smith had been replaced as leader by Sen. John Sampson, head of the Democratic conference. Sampson, with Adams’ assistance, then steered the selection process to back AEG for the governor to approve.

“The Inspector General confirmed that from the inception of the process, AEG was a favorite of the relevant Senate decision makers, first Senator Smith and then, after the so-called ‘coup’ in the summer of 2009 which changed the leadership of the Senate, Senators Sampson and Adams,” the report noted.

The IG report said investigators “found a pattern of the Senate disclosing internal Senate information to AEG throughout the process, information which AEG could then use to its competitive advantage.”

The report also found evidence of a pay-to-play arrangement in which the Democratic Senate campaign committee solicited donations from AEG for select senators, including Adams. And the inspector general made a point of stating that Adams had provided evasive and, at times, dubious answers to investigators’ questions.

The 2010 report was referred to federal prosecutors but no charges followed. Adams was never accused of breaking any laws, and he has repeatedly defended his actions over the years by stating that the investigation did not lead to charges of illegal activity.

‘Inaccuracies and Errors’

On Sunday, Adams, now Brooklyn borough president, struck a similar tone in a statement provided by his mayoral campaign. His campaign did not fully address a list of questions from THE CITY stemming from the 75-page transcript.

“I created a walled-off process and always held myself to the highest ethical standards—and there is zero evidence my decisions were based on anything other than what I believed was best for New Yorkers,” Adams said. “In fact, the process I created yielded millions-of-dollars a year for our schools and thousands of jobs for our state.”

He also slammed the IG’s report as “full of inaccuracies and errors,” arguing that the probe was driven by Republicans seeking to derail Democrats in elections that were upcoming at the time.

“It is absurd that I am still responding to a political hit piece created to discredit me a decade after the original false accusations were made — and unsubstantiated,” Adams added.

The IG’s report resurfaced during the mayoral campaign’s first in-person debate June 2 when Adams’ chief rival, tech executive Andrew Yang, accused him of being involved in a “trifecta” of corruption investigations at the local, state and federal level. Though Yang did not mention the Aqueduct probe, his “trifecta” reference certainly hinted at it.

The transcripts obtained by THE CITY reveal a pattern of evasiveness during the one hour and 25 minutes Adams was questioned the afternoon of May 13, 2010, by IG lawyers Philip Folglia and Felisa Hochheiser inside the inspector general’s office in Lower Manhattan. The answers he provided were made under oath.

Foglia died of COVID-19 last year. Hochheiser did not respond to THE CITY’s questions.

Mixed Memories

At times, Adams’ memory when talking to investigators appeared to be sharp.

He was able to recall minute details of AEG’s proposal (“They were going to install 3,200 [slot] machines in seven months and two weeks.”) and named off the top of his head the last year he’d attended a church service led by former Queens Rep. Floyd Flake, who is also a pastor (1985).

But on other questions relating to AEG’s lobbying and fundraising, he often professed a loss of memory, repeatedly stating, “I don’t recall.”

The investigators were trying to determine Adams’ role in the selection of AEG for a 30-year franchise to operate a casino at the struggling South Ozone Park racetrack. The winner would contribute a portion of their revenue to the state, which was banking on a flood of bettors losing millions.

AEG won out over four other bidders in January 2010, just a few months after the Havana Room fundraiser. A key player in making that happen was Andrew Frank, the AEG lobbyist who attended Adams’ birthday bash.

A transcript of Frank’s interview by the IG shows that when investigators asked him about the Havana Room event, he — unlike Adams — remembered the night vividly.

That night, Frank told the IG, he brought along “five or six” AEG partners with the intention of writing campaign checks for Adams.

Frank recalled that the first thing the AEG partners noticed was the presence at the party of one of their rivals for the casino franchise, New York City entrepreneur Don Peebles, who had submitted a bid in partnership with MGM.

At one point during the event, Frank said, Adams gave a shout out to Peebles.

“I was very impressed with him at the dinner and I thought that going there and him saying he recognized Mr. Peebles when there were a few AEG people there, I thought was — I respected that tremendously. He didn’t recognize or honor or recommend any of the others, but I like what he stood for and stands for,” Frank said. “A couple of our partners thought, ‘That’s really nice, we just came to his fundraiser and he is acknowledging the opponents.’”

The IG lawyers showed Frank an email he sent to AEG partners days before the event, in which he spells out the importance of attending the bash to the mission of gaining Adams’ support: “Team we will absolutely need to be present at this event for Senator Adams.”

Asked why he considered attendance at Adams’ fundraiser essential, Frank replied, “He was the racing and wagering chairman.”

He added: “We felt that it would be important for us as AEG to be there. A couple of our lobbyists recommended it highly and so we went. It was a normal fundraiser. There were probably, I don’t know, 50 or 100 people there.”

Peebles told THE CITY he recalled Adams’ speech at the fundraiser in part because of his political ambitions.

“What struck me is he talked about running for mayor of New York back then,” said Peebles. “He indicated that as mayor he would further advocate for black businesses, minority-, women-owned businesses.”

‘We Don’t Have a Choice’

The day after Labor Day, four AEG-related entities each sent a check to Adams totaling $7,500. That was followed two days later with $1,000 from Frank and $3,000 from Las Vegas-based AEG partner Larry Woolf, campaign finance records show.

There’s no record of Peebles donating a dime to Adams that year, although another Aqueduct bidder, Delaware North, also wrote a $500 check to Adams a few days after the Havana Room event.

A spokesperson for Adams’ campaign noted that lobbyists for a number of bidders — not just AEG — contributed to Adams fundraising efforts at the time. Frank did not respond to inquiries by THE CITY.

The transcript shows that Frank also told the IG that in December 2009 — a few weeks before AEG was picked for the Aqueduct franchise — a contact at the Democratic Senate Campaign Committee asked him to raise more donations for five specific senators. Among them: Adams.

The Democratic committee was “doing their outreach before the filing deadline and they contacted me,” he said. “They contacted me and said ‘We would be appreciative if you could help raise money from AEG, your partners, for these five individuals.’”

Candidates for NYC mayor told us where they stand on 15 big issues. Now you can pick your positions and see which contenders are the right ones for you.

He said he asked several partners to write checks, but some had already done so and declined to pony up more money. In the end, Frank said, he was able to pull together $3,000 donations for each of the five senators — less than the $5,000 the committee asked for. Records show two AEG partners each wrote $1,000 checks to Adams’ campaign in early January 2010.

Asked what part the five senators played in the Aqueduct franchise selection, Frank said four of them had no role. Only one did: “Sen. Adams, yeah, because of his role as the racing and wagering chairman.”

With yet another request for donations from Sampson, Frank spelled out the transactional nature of the sought-after political contributions.

“This is the kind of stuff we have to make decisions about from a financial perspective. This is the Brooklyn group that is important to Senator Sampson. He is also having a fundraiser next Tuesday night. I encourage the same participation from our team as we did with Senator Adams,” Frank wrote in an email to one of AEG’s backers.

The recipient of the email replied, “Sounds like we don’t have a choice but to do it.”

A Meeting with Al Sharpton

Several times during his session with the IG’s lawyers, Adams appears to have made statements that were contradicted by records the lawyers showed him.

During one inquiry, the Rev. Al Sharpton was raised. The IG lawyers asked Adams if Sharpton was involved in seeking support for AEG. Adams said flatly that he was not.

But the IG then produced an email describing a meeting Adams was told about that included Sharpton, Sampson, an AEG partner and Gov. Patterson.

Adams then said the meeting never happened. Sharpton did not respond to a phone message from THE CITY.

Adams was also asked by investigators whether Sharpton had been at the birthday fundraiser at the Havana. He said he couldn’t recall, but pointed out that Sharpton frequents the club, so that he might have been there.

“If he attended,” said Adams, “he sure didn’t leave a check.”

The Adams campaign spokesperson said Sunday that while Sharpton hadn’t been invited, he was at the Havana that night, and that Adams briefly said hello.

Adams also told the IG lawyers he never spoke directly with Christopher Higgins, the Senate counsel who was in charge of producing the analysis used by the Senate to pick a bidder.

But Higgins told the investigators he did speak directly with Adams and expressed concerns that all the bidders’ revenue projections were inflated and “outrageous.”

Adams did not respond to THE CITY’s question about his interactions with Higgins during the Aqueduct bidding process.

Adams said he instructed his staff never to release any of the internal Senate documents spelling out the specifics of each bid. But when asked by the lawyers for the inspector general whether it would be improper to release such information to bidders, he said the information was never explicitly described as secret.

“It was never really confidential,” he said when asked. “So I don’t want to make an assumption about proper or not proper.”

Adams goes on to say that he believed memos from his own staff to him were in fact confidential, but he couldn’t say the same for memos he received from Senate staff.

“It was really undeclared whether they were public or not. It wasn’t put in whether they were. I really don’t want to state. It was just unclear,” Adams answered. “I treated my staff one way. I really don’t know what took place outside of my office.”

In his final report, the IG questioned Adams’ responses. Adams had told investigators he’d never actually read the bid information he was supposed to review — including the insider info that was leaked to AEG.

Adams said “reading the documents was something that I just didn’t have time to do.” He said he only looked at graphs that were attached to the voluminous reports examining the different bids.

As the IG noted, “Aside from the obvious disregard for the analysis and diligence involved in creating these documents, it seems reasonable to expect the chairman of the Racing and Wagering Committee in the Senate to actually review all proffered information thoroughly before recommending a vendor for a 30-year contract that meant billions of dollars to New York State.”

Adams ‘Strains Credulity’

Then-Gov. David Paterson told investigators about a meeting with Adams and Sampson in a restaurant where the two pressed him to support AEG. Adams said he’d only happened upon Paterson, Sampson and an AEG partner at the restaurant and that he made no such recommendation.

The IG found Adams’ explanation “strains credulity,” in part because it was contradicted by both Sampson and Paterson.

“Sometime in January I had dinner with Senator Sampson and Senator Adams, whereupon they formally asked me to join them in proposing AEG, so as to convince the Speaker and get this process over with,” Paterson told the IG’s office. “And this is the first affirmative step that anyone has taken.”

Paterson couldn’t remember where the meeting had occurred. But asked when it happened, Paterson noted that it was documented on his calendar.

“On January 8th, I’m scheduled to have dinner with Sampson and Senator Adams,” he told investigators.

Sampson also confirmed that the dinner had taken place, answering “yes” when he was asked if he had dinner with the governor in January 2010.

“Was Senator Adams in attendance?” one investigator asked him.

“Yes, yes. Now it brings it back,” said Sampson, who subsequently responded five times that he couldn’t recall what had been discussed that night.

However, Adams told investigators that he had just coincidentally bumped into Paterson, Sampson and an unidentified rep for AEG having dinner at a restaurant somewhere on 57th Street.

He could only place that incident as having occurred “recently,” sometime earlier in 2010.

“The governor was at a restaurant when I stopped by and Senator Sampson was there and I believe someone was there from AEG,” Adams told investigators. “I just said hello to them and I moved on. So I don’t know if that’s considered a meeting.”

One of the investigators asked Adams whether that means he left after saying hello.

“I went to another part of the restaurant,” he answered.

In January 2010, then-Senate Leader Sampson, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver and Paterson tentatively awarded AEG the franchise to run the Aqueduct casino.

Within months, details of the backroom maneuvering surfaced, and by March 2010 the state removed AEG from the running. The casino conglomerate Genting ultimately won the lucrative gig.

As the IG noted, “Embodying the dubious nature of every aspect of the selection process which culminated in the tentative selection of AEG…the circumstances surrounding AEG’s ultimate selection are murky and fraught with political considerations predominating over the public interest in expeditiously awarding the franchise to the vendor who could maximize the benefit to the state.”

Of No ‘Great Importance’

Despite his leadership of the gaming committee, Adams downplayed the significance of his role in the racino process at several points throughout the IG interview.

“My role was merely to speak with Senator Sampson and give him my recommendation, my nonbinding recommendation,” he said at one point.

He later added, “As hard as it may seem, I didn’t have any vision of my importance because I didn’t have great importance.”

Adams also characterized himself as a newbie legislator when asked whether he considered the casino deal process a “procurement.” This was asked in the context of the confidentiality of the bid documents.

Earlier in the interview, Adams had wrongly stated that he was elected to the state Senate and first took office in 2007 — even though he was elected in 2005 and took office in 2006, three-and-a-half years before the bidding process began.

“I was too young in the Senate. I probably didn’t even know how to spell procurement, to be honest with you,” he said to investigators. “I didn’t know exactly what a procurement process was. This was new to me.”

This article was originally posted on Eric Adams’ Aqueduct Casino Bid Scandal Interview Transcript Reveals Contradictions and Shaky Memory