For some Texans who lost loved ones to the coronavirus, lifting the mask mandate is a “slap in the face”

What confuses Delia Ramos about Gov. Greg Abbott’s recent decision to cast off coronavirus restrictions in Texas isn’t his order to let more people into restaurants. The Brownsville school counselor knows people are hurting economically.

But with more than 43,000 dead in Texas — including her husband — is wearing a mask in public too much to ask? At the least, it could take pressure off the medical systems and help prevent more people from dying, she said.

“It’s not about taking away anybody’s job or making anybody else suffer financially because everybody has their families to take care of,” said Ramos, who lost her husband Ricardo to the coronavirus last year.

“People can go pick up groceries, people can go into a restaurant and people can shop around the mall in masks,” she said.

Abbott’s Tuesday declaration that it was time to “open Texas” has been decried by local officials and health experts, who say it’s too soon to become lax with coronavirus restrictions, as just 7% of the state’s residents have been fully inoculated against the virus. President Joe Biden likened the decision to “Neanderthal thinking,” and an official with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said it’s not the time to loosen precautions.

But the announcement hit harder with Ramos, and others who have lost spouses, parents or friends to the virus — in some cases, making them wonder if the deaths of their loved ones meant nothing.

It feels like people that think it’s “inconvenient to wear a mask” override all the “people that have been lost” to the virus, as well as doctors and nurses working long hours and teachers scared to go to work for fear of being exposed, Ramos, 39, said.

She’ll continue to wear her mask “with honor.”

“I don’t want other children to grow up without a father, the way that mine unfortunately are going to have to grow up without one,” she said.

After teasing an announcement for days, Abbott said Tuesday that masks would soon no longer be required statewide, and that businesses could return to full occupancy starting next week.

From a Mexican restaurant in Lubbock, Abbott said the state is in a “completely different position” now that vaccines are available and there is broad awareness of prevention measures. He also said there is more protective equipment, testing and treatments, and he cautioned Texans to exercise personal vigilance.

The governor’s spokesperson, Renae Eze, said he “joins all Texans in mourning every single life lost to this virus, and we pray for the families who are suffering from the loss of a loved one.”

“As the governor has stressed repeatedly, removing state mandates does not end the need for personal responsibility nor the importance of caring for family members, friends and neighbors,” she said in a statement.

Abbott’s order — which makes Texas the most populous state without a mask mandate — comes as virus variants that are more contagious have emerged in Texas, with Houston becoming the first city nationwide to record cases of every major variant, according to a recent study.

The announcement also comes before a spring break period that could send people traveling across the state, timing that makes Dr. Jamil Madi, in Harlingen, think “we’re shooting ourselves in the foot.”

“The virus is still here, it’s not like it’s faded away,” said Madi, chief of critical care medicine and director of the intensive care unit at Valley Baptist Medical Center in Harlingen. “The virus is just dormant and the way it wakes up is by human contact.”

Texas has seen infections and deaths from the virus drop, and hospitalizations are at their lowest point since October. But the state ranks nearly last among states for the share of its population that have gotten a shot, and the number of patients hospitalized with the virus is higher now than it was when Abbott first began a phased economic reopening of Texas last spring.

In the hard-hit Rio Grande Valley where Madi works, infections went into a lull in September and early October but have picked back up, he said. There was a wave after the winter holidays when people traveled and gathered with family members to celebrate, and he’s seen patients who had the disease and recovered return sicker than ever.

“Every time we decide to let loose, whether it’s gatherings or [changes to] mask mandates, we see a definite spike after an event happens,” creating a kind of “roller coaster,” Madi said.

“We go back to the same cycle again and again and we’re tired, we’re all tired, to say the least,” he said.

More than 43,000 people have died with the virus in Texas during the pandemic, which has devastated swaths of the state’s economy and taken a toll on people’s mental health.

Ramos, among those who lost a loved one, found out about Abbott’s orders on Facebook. The next post in her feed asked for prayers for two school district employees fighting the coronavirus in the ICU, she said.

She was struck by the “harsh difference in those two realities.”

In nearby McAllen, Ana Flores watched Abbott’s announcement in disbelief on Tuesday. For the 39-year-old, who works at an adult day care, it immediately brought back memories of when Abbott loosened COVID-19 rules in May — weeks before infections surged and devastated the predominantly Hispanic or Latino communities along the U.S.-Mexico border.

She got severely sick with the virus. Her husband of ten years, a truck driver, who was cautious and “knew a little bit about everything,” was hospitalized and died at age 45.

“For [those of] us who lost a loved one, for us who survived — because I got pretty sick as well … it’s like a slap in the face,” Flores said of Abbott’s announcement, noting his “happy” tone and the “clapping” people around him.

For Abbott to say “it’s time for us to get on with our lives, everything to go back to normal,” she said, “normal is not going to happen for us ever again.”

She said it felt like Abbott “doesn’t care” that counties in the border are “still struggling” even if other parts of Texas are doing better.

Mandy Vair, whose father, a hospice chaplain, died with the virus last summer, saw the order and wondered: Did his death not matter? She and other family members were limiting social activities and wearing masks, but were infected in November and Vair was sick for weeks. Her family still hasn’t had a memorial ceremony for her late father because they don’t feel it’s safe to gather.

She said Abbott’s decision made her think, “He got his immunization and maybe all of those that are important to him already got the immunization. So [now] the rest have to kind of fend for themselves until their turn comes up,” she said. “We have to be responsible for ourselves — well, haven’t we been trying to be responsible for ourselves the whole time?”

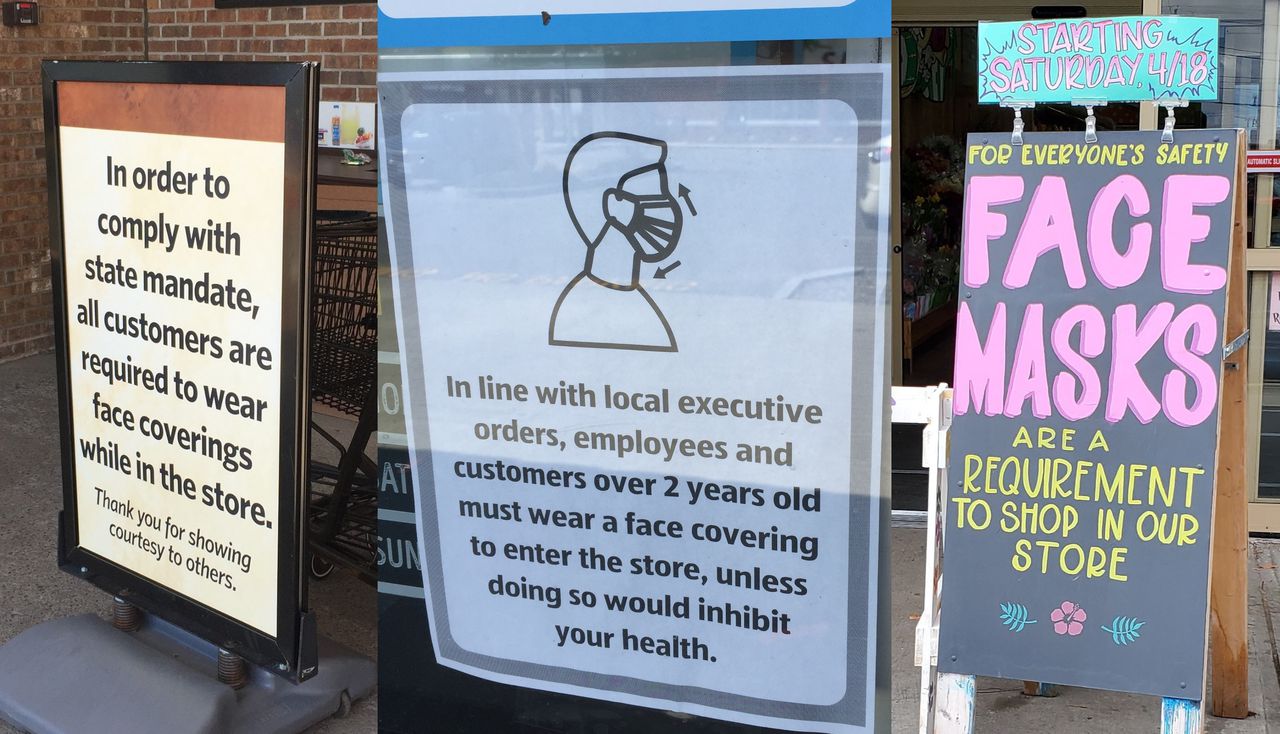

Local officials have slammed Abbott’s order, saying it’s premature and sends the wrong signal to residents who take cues from their leaders about how seriously to take the virus. Some have also expressed worry that front-line workers and communities of color could be left vulnerable to infection if others aren’t required to wear masks around them. A CDC website says wearing a mask protects the wearer and those around them, and works “best when everyone wears one.”

More than half of the COVID-19 deaths have been Black or Hispanic people, and advocates fear these communities have fallen behind in the vaccination efforts in Texas. In Texas, fatality rates in border areas like El Paso and Hidalgo, where a majority of residents are Hispanic or Latino, were among the highest per capita of big counties statewide.

State Sen. Borris Miles, a Houston Democrat, said on Twitter that Black people have a disproportionate fatality rate and that the governor lifting a statewide mask mandate amounted to “signing the death warrants of communities of color.”

“Today he made it clear Black lives don’t matter,” Miles tweeted.

Rebecca Fischer, an epidemiologist at Texas A&M University, said she was surprised such a “drastic measure was taken at such a critical time” and thinks the state could face “potentially a devastating trajectory” if prevention measures are relaxed.

Now is “not the time to be dropping our masks or throwing them in the trash can. This is the time really to be stepping up our prevention behaviors,” said Fischer, an assistant professor with A&M’s school of public health.

Public health experts have recently said two masks may be better than wearing just one, given differences in how they are constructed and fit, she said.

Eze, with the governor’s office, said Abbott will continue to work with other officials to “speed the vaccination process to protect Texans from COVID, with the immediate priority of vaccinating Texans who are most likely to be hospitalized or lose their life from COVID.” She cited a state initiative that deployed the National Guard to help vaccinate homebound seniors.

She said Texas “has the tools and knowledge we need to deal with COVID and keep Texans safe,” and that the number of vaccines is “rapidly increasing” each day and more Texans are protected.

Abbott has also said local judges can reimpose some restrictions if COVID-19 hospitalizations exceed 15% of capacity in their region for seven straight days.

But Hidalgo County Judge Richard Cortez said he doesn’t want to wait until that point to be able to take action.

He said he was “very concerned” about Abbott’s decision, and did not receive advance notice of the order.

Between the vaccinations and people who have contracted the virus, Cortez estimated about a quarter of his residents have some immunity to COVID-19.

“But we still have a long way to go,” he said. “[Abbott] said from the very beginning that he was going to let science dictate his actions. Well, science tells us to have physical distance and separation, facial coverings,” and to take other precautions.

What was “so special, what was so scientific” about having Texas’ Independence Day be the day that the announcement was made, he asked.

In El Paso, city and county leaders urged their residents to practice the unity that helped them weather several recent tragedies, including a mass shooting in 2019 and a flood of coronavirus infections last fall. Just a few months ago, officials had to ask jail inmates to work for $2 an hour moving bodies, because regular staff couldn’t keep up with the demand.

County Judge Ricardo Samaniego said COVID-19 patients were still taking up some 14% that of the region’s hospital beds, indicating the area isn’t ready to reopen.

“The timing is really what the problem is,” he said. “If, in fact, it were true that we were ready to open, it’d be exciting for everybody, we’d be celebrating.”

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton sued Samaniego last fall after the county judge imposed tighter restrictions than the state on business openings. Paxton won, and in his victory lap on Twitter referred to Samaniego as a tyrant and El Paso County, the state’s sixth largest, as a “rogue subdivision.”

Samaniego said he doesn’t expect that kind of interference again because he knows he’s limited in what he can do moving forward.

“We’re not going to do anything that is outside of the legal components and legal elements [of the order],” he said. “We’re going to look more at trends and we’re going to talk to all the leaders and consult with the county-city task force. We’re going to check the science before we check the politics.”

El Paso Mayor Oscar Leeser said his plea for El Pasoans to continue wearing masks came not just from his duties as an elected official. Leeser’s mother and brother died from the disease less than two months apart in 2020.

“My mother was sick and we didn’t realize that my mother had COVID-19. But I said ‘Guys, make sure you wear your mask,’” Leeser recalled telling his brother and sisters late last year. His sisters listened but his brother didn’t, he said.

“My brother did not wear a mask while he was there and unfortunately got COVID-19 and also lost his life,” Leeser said. “I am a living testimonial that it works.”

Meanwhile, the executive director of Operation H.O.P.E., an El Paso charity that helps families pay for funerals, said he’s not talking to a dozen or more families every day the way he was in late 2020, when the border city was the country’s COVID-19 epicenter.

But Angel Gomez, the executive director, said he’s not optimistic that won’t happen again.

“I just hung up with the seventh [family] today,” he said. “We should have just waited a little bit longer, but with this governor it’s like we take one step forward and two steps back.”

“Give it until the end of April and we’re going to start seeing a spike again,” he added.

Flores, in McAllen, remembers when Abbott loosened the coronavirus restrictions in May. She and her husband were scared. He traveled all over Texas as a truck driver, and would call her saying he’d gone into a store and saw few people were wearing masks. She remembers seeing a newspaper headline describing South Texas as a “Valley of Death” — an apropos description to her at the time.

“Look what happened the first time around, that’s when we got hit really bad especially here in the Valley. … All these people that were sick and dying, my husband included. I just feel like it’s too soon again.”

She’s going to keep wearing a mask. If her husband were alive — if he “wouldn’t have been taken from” her — she thinks he would, too.

This article was originally posted on For some Texans who lost loved ones to the coronavirus, lifting the mask mandate is a “slap in the face”

This article was originally posted on For some Texans who lost loved ones to the coronavirus, lifting the mask mandate is a “slap in the face”