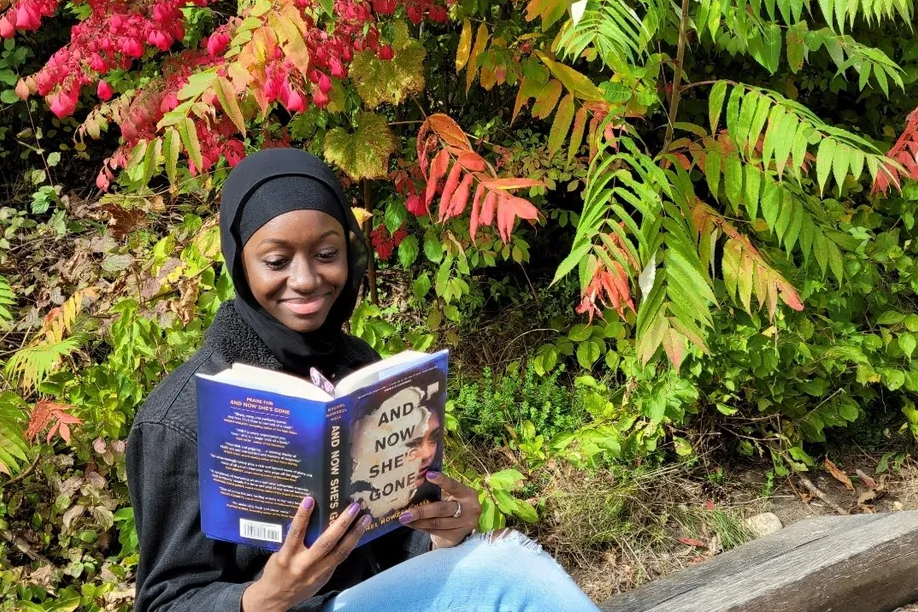

This Harlem teacher shares her love of literature and how she’s promoting diverse authors

Growing up in the Bronx, books provided an escape for Fatuma Hydara, who, as the eldest daughter in a Muslim family of West African immigrants, shouldered many household responsibilities.

Because of her love of books, she decided at a young age to pursue a career as a librarian, in book publishing, or as a teacher. After a summer internship at HarperCollins showed her that cubicle life wasn’t for her, she opted to become a teacher. She’s been in the classroom for the past eight years.

Hydara teaches English to eighth graders at Harlem’s Neighborhood Charter School, where her background has helped her connect with students and parents who are also Muslim and West African. Some of those families, her own included, have connections to the Bronx neighborhood where New York City recently saw one of its deadliest fires in decades.

Hydara’s background also inspired her to start her own virtual book store, Tuma’s Books and Things, where each month she curates a selection of books from authors who identify as Black, indigenous, persons of color and/or queer.

“My mission is to ensure that ALL identities can find stories that reflect and honor who they are, while allowing others to learn about people who might be different from them,” Hydara said.

She also sits on the Council of Educators for RetroReports, a journalism nonprofit that creates classroom-friendly videos aimed at connecting history to current affairs. She is one of 20 educators from across the nation in the organization’s inaugural council, tasked with helping create lessons to accompany the videos.

Hydara spoke with Chalkbeat about being a bibliophile, the importance of having teachers who look like her, and how this school year has been more challenging than any other. .

Tell us more about your love of books and how that inspired you to create your own virtual book shop.

Growing up, I had a limited and sheltered childhood. As the oldest daughter of West African immigrants, I had a lot of responsibilities in the home — caring for my siblings, doing chores, and helping my parents navigate America as a translator. I didn’t get to have a lot of experiences or explore different places. But books opened up worlds for me instead.

As much as I loved reading and books, I never encountered characters like me — Black, Muslim, First Generation, West African girls. And I didn’t even realize it as a problem until I got older and read Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Reading my first African writer felt like coming home after years of being away.

Does your school serve students from the West African region your family comes from? I’m wondering how important you think it is for those students to see you in your role as a teacher.

Yes, there are West African students, and that is a major part of what I enjoy about working at this school. I think it’s definitely important as I am able to connect to those students on a personal level. They share information about their family lives that they don’t with other teachers. I am able to communicate with their families in ways that they value and understand. I knew my presence made a difference when on the first day of Ramadan, a student I do NOT teach came into my classroom, asked if I was fasting, said ‘me too’ when I replied affirmatively and asked for a fist bump.

Did anyone at your school — or even yourself — have any connections to the community or the victims of the tragic fire in the Bronx? We had heard that it has been hard on that tight-knit community, largely of Muslims from Gambia and other West African countries.

Yes, I used to live in another building owned by the same corporation that is only a few blocks away. My parents still live there. I have lots of friends who lived in the building and a close friend who lost her sister. Many of my friends and I came together during those first few horrible days to support as much as we could. It was astounding how much money the community was able to raise and all of the supplies we gathered to take care of our own.

Have you found this year to be more difficult than previous ones given the prolonged time that students were out of the physical classroom? Are you seeing anything different with your students?

This year has definitely been different. Many students are used to (and prefer) the looser routines from home. While my school had a solid online program, there were many students who did not log on Zoom or [do so] on time. They logged off early for chores or to run errands. They simply didn’t complete work. Given the extenuating [circumstances], we passed all students, but it instilled bad habits and a concerning mindset in students.

Most students started the year believing they didn’t need to work for their grades. They didn’t value putting in hard work. Students’ attention spans offline and without tech have become shorter than ever. Reading and writing stamina is lower than I’ve ever experienced in my career.

Tell us about a favorite lesson to teach. Where did the idea come from?

One lesson I love is my intro to Macbeth by Shakespeare. I set the scene by closing the blinds and finding thunder/lightning sounds on YouTube. And I read the lines of the three witches with the sound effects. It immerses students immediately in understanding mood, and in later scenes, they have a deeper understanding of why Macbeth should be cautious of the witches.

What’s something happening in the community that affects what goes on inside your class?

My school is located in Harlem on a very high-traffic street with a police precinct located in the subway. I think my students are affected by the same things many urban NYC kids are — poverty, drug use, homelessness, mental health, etc. Many of the families we work with were impacted by the pandemic and its financial constraints. Nearly 100% of our students qualify for free lunch.

What part of your job is most difficult?

What I struggle with most is balancing work and life. The long school day of a charter school drains me, and I’m often too tired for much else when I get home. I would also love to continue learning and enhancing my craft but attending outside [professional development sessions] is a schedule nightmare due to lack of coverage.

What was the biggest misconception that you initially brought to teaching?

I thought schools were well-oiled running machines, but there are lots of moving parts in terms of roles. If one part isn’t doing its job, others have to overcompensate, or it begins to unravel. I realized quickly that teachers are the backbone of the educational system, but our role is often devalued and our voices silenced.

What’s the best advice you’ve received about teaching?

You can’t do everything, and you can’t help everyone. Many things are literally beyond your capacity as an educator. As one teacher in a long line that a child will have, you can only do your best and then pass the torch.

This article was originally posted on This Harlem teacher shares her love of literature and how she’s promoting diverse authors