Army report finds Fort Hood soldier Vanessa Guillén reported being sexually harassed twice before she was killed

A U.S. Army investigation found that Spc. Vanessa Guillén reported being sexually harassed two times by a fellow soldier at Fort Hood before she was killed, a finding that contradicts the Army’s previous claims that there was no evidence Guillén experienced harassment.

Guillén’s supervisor and other officials failed to report the harassment up the chain, according to a report released Friday which provided new details about the investigation following Guillén’s disappearance on April 22, 2020.

Investigators did not find “credible evidence” that Spc. Aaron Robinson, the man accused of killing Guillén, sexually harassed her or that they had a relationship outside of their professional one, the report said. However, Robinson was reported for sexually harassing another female soldier. Robinson shot and killed himself after being confronted by the police.

As a result of the investigation, Army officials removed five current or former leaders in the 3rd Cavalry Regiment, where Guillén also worked, from their leadership positions. Three of those officers will also be reprimanded. Garrett also referred disciplinary action against eight other officers — all of whom will receive reprimands and one who will be relieved.

As of Friday, 21 officers in total have been suspended, relieved of their positions or given official reprimands following Guillén’s murder.

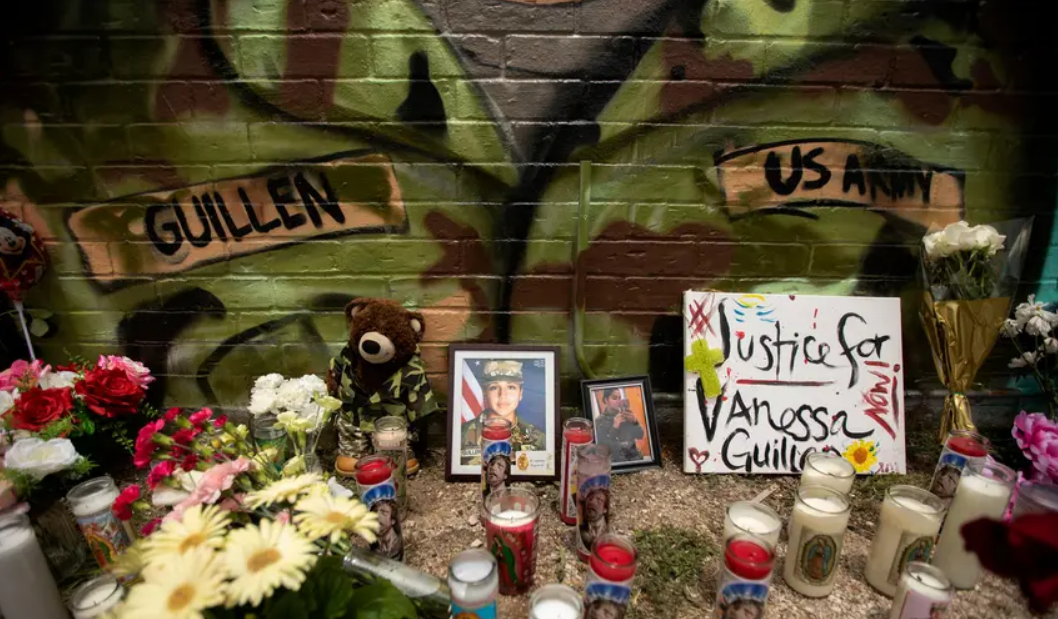

Guillén was found in a shallow grave outside Fort Hood after being bludgeoned to death last year. She was 20 years old. Her killing sparked national outrage and calls for reform in the military against sexual harassment and violence.

“I have a daughter who is 23 — the same age as Vanessa, if she was here with us today,” Maj. Gen. Gene LeBoeuf said in a press call with reporters Friday. “I keep a picture of my daughter on my desk. When I speak with the Guillén family I can see my daughter there. And each time I imagine the grief of the entire Guillén family.”

The secretary of the army said in August that Fort Hood had “the most cases for sexual assault and harassment and murders for our entire formation of the U.S. Army.” At least 159 Fort Hood soldiers died out of combat between 2016 and last year, including seven homicides and 71 suicides, according to an analysis by The New York Times.

But advocates for military sexual assault victims say the problem is bigger than just Fort Hood. They say the military creates a siloed environment allowing sexual harassment and sexual violence to occur, many times unnoticed and unreported. And when there are reports, the military handles the investigation itself. Her family continues to call for widespread reform.

A Pentagon panel recently recommended that decisions to prosecute service members for sexual assault be made by independent authorities, instead of military officials — a reversal of the longstanding practice of handling these cases internally.

The report released Friday is separate from the investigation overseen by the U.S. Attorney’s Office and in collaboration with FBI and did not consider criminal allegations.

According to the report, Guillén told a supervisor that another supervisor had made sexual comments toward her in the summer of 2019, according to the report. That supervisor made comments in Spanish suggesting they wanted to have “a threesome” with her, Guillén said. Two other soldiers also reported the incident to supervisors, who failed to initiate an investigation.

Another time, Guillén said the same soldier approached her while she was washing herself in the field and said they tried to “watch her wash up.” The Army investigator discovered a pattern of mistreatment from the supervisor but said it did not appear related to her killing.

The Army has not released the name of the individual accused of sexually harassing Guillén, which LeBoeuf said was because they were not a high-ranking officer and to allow for “due process.”

“We found many inconsistencies in this report. Vanessa’s case was severely mishandled, and therefore this report reflects a lot of damage control,” Guillén family attorney Natalie Khawam said in a statement to The Texas Tribune. “We are troubled that the names of the soldiers that sexually harassed Vanessa are being omitted. It’s heart breaking and frustrating for all of us.”

Khawam said the report shows why reform from the I Am Vanessa Guillen Act is necessary. The act, introduced last year, would create a confidential reporting system for sexual harassment in the military and explicitly list sexual harassment as a crime in the military law constitution. Lawmakers plan on reintroducing the bill this year.

“This all should have never happened and our soldiers deserve to be treated like human beings,” Khawam said.

The report also detailed a timeline of when Guillén went missing and of attempts to locate her. Robinson was put under observation but was able to slip away on June 30. LeBoeuf said no additional details could be released because of the criminal investigation that is ongoing.

Investigators concluded that Army officials failed to effectively communicate with the community, the media and Guillén’s family — but said officials appropriately jumped into action when she went missing. The Army also needed a better way to classify her disappearance, the report said. Army officials temporarily labeled her as AWOL — absent without official leave — because “they lacked sufficient evidence to support a missing status determination,” according to the report, even though officials knew the circumstances of her disappearance were suspicious.

“However, the Army’s policy requiring an AWOL duty status sent the wrong message, creating an inaccurate perception that she had voluntarily abandoned her unit and limiting the command’s access to certain resources, such as casualty assistance officer to liaise with the family,” a statement accompanying Friday’s report said. “The Army has since published a new policy on duty status of missing Soldiers to correct these gaps and ambiguities.”

The Army previously announced it is restructuring its criminal investigation command, as well as redesigning its sexual harassment and assault response and prevention program as part of an initial swath of adopted changes.

Officials have updated policies to require full investigations of off-post soldier drug overdoses, including of the source of the drugs, and investigations of all suspected solider deaths by suicide. Last year, the Army updated guidance on how to respond when a soldier goes missing. Officials also are requiring changes to improve the climate and requiring regular welfare checks at Fort Hood.

More changes are to come as investigations continue, LeBoeuf said.

“None of this will bring Spc. Guillen back,” LeBoeuf said. “[But] her memory drives us to be better.”

If you or someone you know has been sexually assaulted, you can receive confidential help by calling the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network’s 24/7 toll-free support line at 800-656-4673. You can also visit their online hotline here.

This article was originally posted on Army report finds Fort Hood soldier Vanessa Guillén reported being sexually harassed twice before she was killed