As schools hire teachers and counselors, a funding cliff looms

The schools of Greeley, Colorado are in the midst of a hiring spree.

The 27-school district, about an hour north of Denver, plans to hire 12 social workers, eight counselors, seven attendance monitors, another seven credit recovery specialists, five health aides, three nurses — plus 46 teachers.

The spending, and similar hires in school districts across the country, are being made possible by unprecedented sums of federal coronavirus relief money. But those dollars can only be used for the next few years. Unless lawmakers increase funding over the long term, districts will face a steep “funding cliff.”

That has experts and school officials debating how to balance what students need now with their balance sheets down the line — and whether it’s responsible to use relief money to add large numbers of staff.

“When we ask CFOs what they’re worried about, they immediately go to: the money isn’t reoccurring,” said Marguerite Roza, who runs Edunomics Lab, an education finance think tank. Hiring counselors and teachers now, she said, means districts could be “stuck going through very painful layoffs in two years.”

On the other hand, many educators and families are clamoring for additional academic and mental health support after more than a year of disrupted school, and research suggests that these investments could help. If this isn’t the time to hire people, they’re asking, when is?

“Our kids need people,” said David Simpson, a middle school principal in Grand Rapids, Michigan. “Our kids need the resources now.”

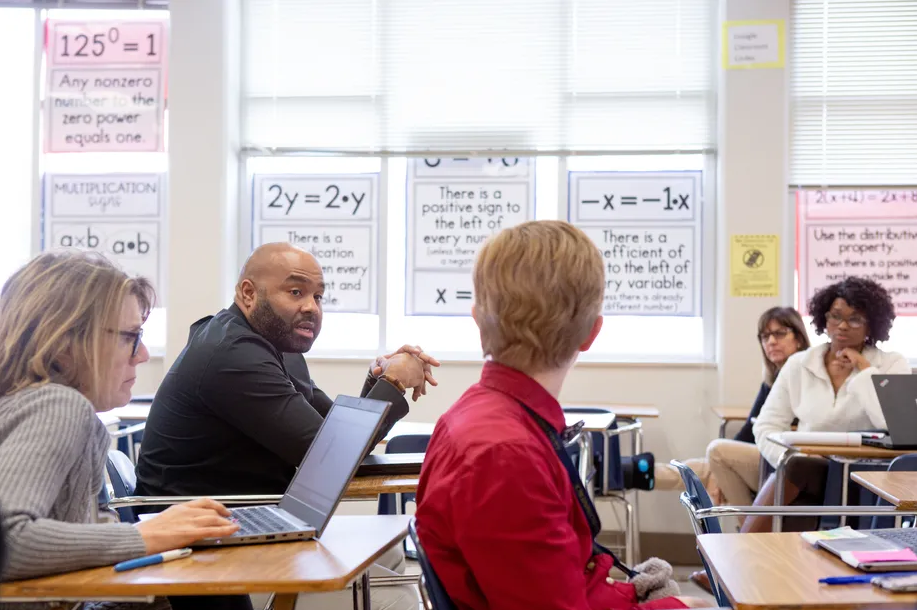

Schools are adding teachers, counselors, and social workers

Greeley is not alone. New York City is hiring teachers to reduce class sizes or add co-teachers in more than 70 schools, plus hiring 500 social workers. Schools will get additional money they can use to add staffers, too.

“Now, they will have money to hire new teachers, art, music, gym, you name it,” said City Councilman Mark Treyger.

Detroit is planning to add enough teachers to substantially reduce class sizes. Chicago is hiring dozens of counselors to shrink large caseloads in many schools.

In Grand Rapids, Simpson’s middle school is bringing on another counselor, a coach to support students still learning remotely, a literacy adviser, and an additional language arts teacher to reduce class sizes. With two full-time counselors, one will be able to focus on academics while the other pays special attention to students’ social development and mental health.

“Having the dollars,” he said, “allowed us to reimagine what that counseling role could look like.”

Districts that are hiring say they’re trying to do so carefully by hiring some contract staff or planning not to fill future vacancies.

“We’re asking them to think ahead,” Boston superintendent Brenda Cassellius said of schools in her district planning to add staff. “If this is a priority right now and it’s not a one-time cost, how do you want to sustain this position?” If the position is temporary, she said, schools should be transparent about that with families and staff.

It’s not clear yet how many roles are being added nationwide.Only a handful of 100 large districts’ spending plans emphasized reducing class sizes, according to a review by the Center on Reinventing Public Education, though many more mentioned adding additional mental health and academic support.

Some districts have gone the opposite way, saying they don’t plan to use the new money to hire many new staff because of funding cliff concerns. Aleesia Johnson, the head of Indianapolis Public Schools, said recently that the district is focused on training existing educators, not adding new ones.

“There are 10 additional days in our calendar this year specifically for teacher development,” she said. “If our teachers feel prepared and better supported … then we’ll see the outcomes in the instruction.”

Why staffing is still such an appealing option for schools

As the new school year approaches, students will enter with academic gaps and greater mental health challenges. Some students haven’t been inside a school building for a year and a half. Adding teachers, counselors, and other staff seems like one way to make sure schools can help students navigate the years ahead.

“An overall sense of safety and wellness and connection to school is going to be our number one priority as we come back,” said Susan Arvidson, a lead counselor at the Saint Paul Public Schools in Minnesota, which is adding nine counselors to its previous 150. “All of these students have been a bit lost.”

It’s possible to avoid hiring by paying existing staff more to take on additional responsibilities, like summer school or afterschool programs. That’s happening in many places, but some schools have found teachers reluctant to take on extra work, even for additional pay after such a stressful year and a half.

Adding staff can also be the path of least political resistance. Smaller classes are popular with teachers and parents, while many families are not enthusiastic about alternatives like longer school days. Local unions, which are often politically influential, tend to support more hiring, which adds to their membership rolls.

Regardless, research suggests that students do benefit from additional staff in schools. Having more counselors has been found to reduce student misbehavior and boost college enrollment. Teaching assistants appear to improve test scores. Students tend to learn more in smaller classes, according to a number of studies, although the size of these gains varies.

Research on non-teaching roles remains fairly limited, said Richard Welsh, an education professor at NYU, but is promising. “From what we do have, it tells us that this might not be a bad investment,” he said.

But questions remain about cost effectiveness and the funding cliff

Some are still wary. Roza of Edunomics has criticized the increases in staff in schools over the last several decades as a mistaken use of scarce resources.

“Long-term, I worry about it as a strategy,” she said. “It’s the strategy that we’ve tried for 20 or 30 years — when you have a need, you hire some more people.”

She argues that it would be better for schools to extend the school day or pay existing teachers more to take on additional students, citing a study that projects that test scores would rise if more effective teachers were assigned larger classes.

There is little definitive evidence that those alternative strategies are more cost effective, but there are potential downsides to quickly adding staff. Studies of class size reduction have found that a hiring binge can mean bringing on less experienced or less effective teachers.

This concern may be particularly acute now, during a broader labor shortage. It’s even possible that schools won’t be able to hire all the new staff they want.

In Greeley, schools have hired nine of their hoped-for 12 social workers, but they’re having trouble filling the remaining jobs. School starts next week.

“Social workers are very much in demand right now,” said Theresa Myers, the district spokesperson. “Everybody is scrambling to hire these same positions.”

As many schools move ahead with hiring, the funding cliff looms. The last federal relief money must be spent by early 2025.

It’s also true that such a steep cliff is not inevitable. The future of President Biden’s proposal to more than double Title I funding remains uncertain. If it becomes reality, districts serving students from low-income families could get another big boost, shrinking the funding cliff.

Some say the onus shouldn’t be on local schools to avoid hiring, but on policymakers to provide more sustained funding for schools.

“We’re constantly hoping that our state will come through with additional resources for us,” said Myers. “We’ll see where we are in three years.”

This article was originally posted on As schools hire teachers and counselors, a funding cliff looms