For some kids, remote learning will continue this fall. Can schools make it better?

Detroit Superintendent Nikolai Vitti knows that, despite his best efforts to convince families, not every student will return to his district’s school buildings this fall.

That means virtual learning is here to stay, at least for a while. But Vitti wants it to work differently, with virtual students whose grades or attendance dip getting a formal nudge to return to buildings.

“If the student is not engaging or their grades are low, then I think we need to have a conversation,” Vitti said. “Online learning as a standalone, as the only model that a student is accessing for instruction, is not working for the vast majority of our children.”

Superintendents across the country are grappling with the same question as they look ahead to the fall: How will they teach students whose families choose to keep them home?

Some families may choose to hold off on in-person instruction until their child has been vaccinated — teens will likely be able to get shots by the fall, but it may take until early 2022 for younger children — while others may opt for virtual learning because they see their child learns better that way.

But as the difficulties of remote learning have become painfully clear, school leaders say they’re planning to make changes to their virtual instruction to incorporate lessons learned.

Some are planning to cut back or eliminate teaching done in-person and virtually at the same time. Others will add structures to support virtual students, or set academic bars that students need to clear in order to stay online. Some districts plan to consolidate virtual instruction so it’s offered at fewer schools or are asking state officials for permission to launch more permanent, standalone virtual options.

In one high-profile example, New York City’s mayor said he plans to eliminate hybrid schedules so students are learning either fully virtually or fully in-person. It’s unclear for now if the city will run a virtual program centrally or at individual schools.

“What I think superintendents in our membership are working very, very hard to move past are the kind of overly complicated, sometimes confusing approaches to hybrid learning that, among other things, simply don’t give students the learning time and the time in-person or in contact with teachers and support staff that they need,” said Mike Magee, who heads Chiefs for Change, an organization that works with dozens of school superintendents.

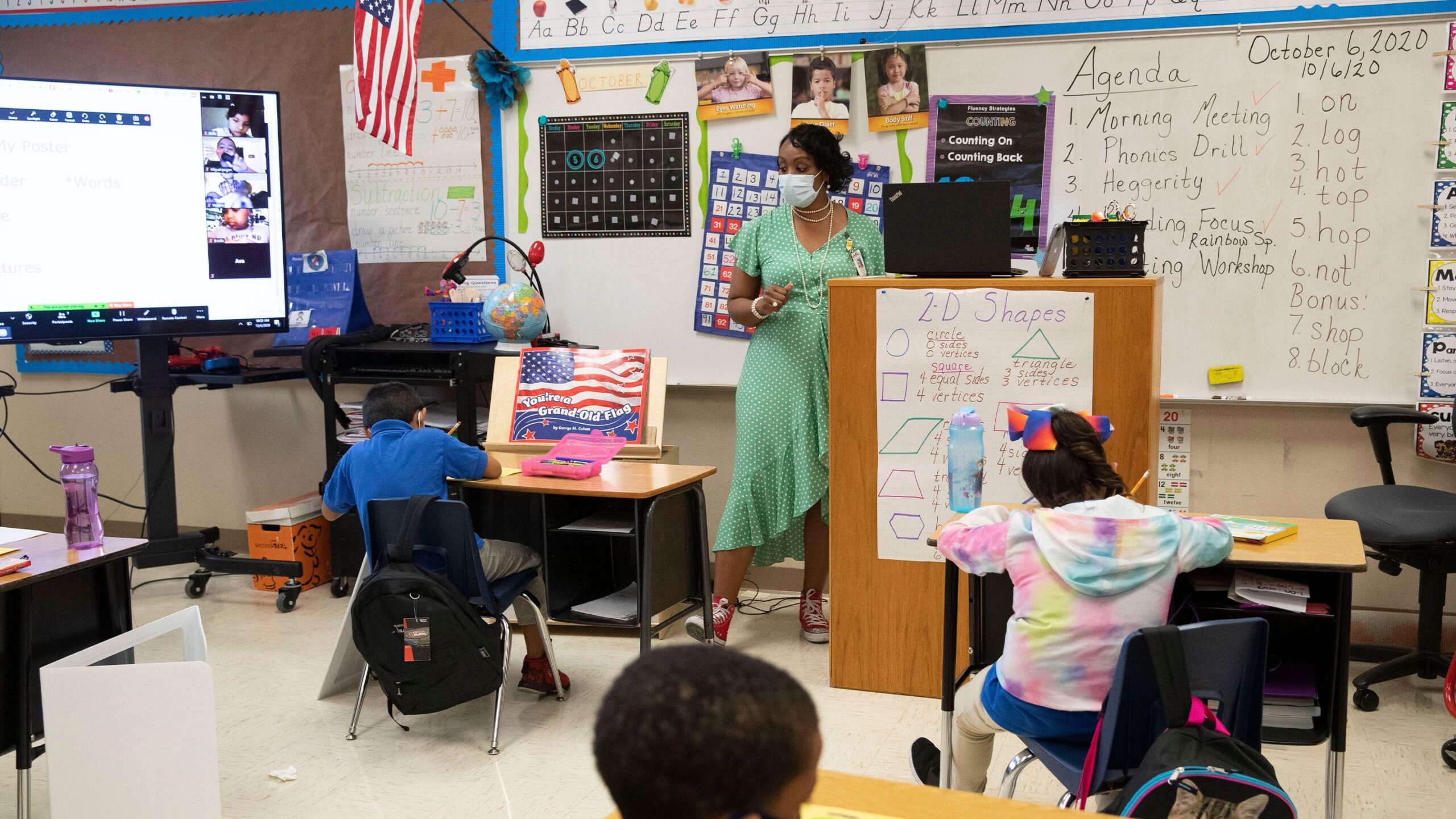

Teaching students in person and online at the same time has been one of the greatest instructional challenges of the last year. Some say it especially short-changes remote learners, and many districts are hoping they’ll be able to stop doing it.

In Fort Wayne, Indiana, about 30% of students remain remote. Superintendent Mark Daniel is hoping that changes by fall, and most of his 30,000 students will return. But elementary schoolers who remain online will be assigned dedicated virtual teachers, allowing the district to avoid the kind of simultaneous instruction it tried at the start of this year.

“Tremendous strain on the teachers, and quite frankly, not best pedagogy,” Daniel said. It was untenable enough that the district hired more elementary school teachers and redid younger students’ schedules mid-year to create more virtual classes.

He’s not sure that separation will be possible for high schoolers, whose course schedules and graduation requirements are more complicated. The district is considering asking teachers who work in person to also carry some virtual students on their rosters — one example of how the pandemic will complicate a third school year.

But he’s relieved that a fully virtual teacher will be fully present for younger students, allowing them to quickly press a mute button if there’s a disruption, for instance. “You can’t do that when the teacher is also trying to teach, if you imagine, 20 first-graders and five or six kids remote,” Daniel said. “Not enough arms.”

As districts move to more fully divide their online students from their in-person ones, it will likely minimize scheduling headaches and ensure teachers can be more focused on the students in front of them. But it may also create a more isolating experience for students who remain virtual, if they no longer interact with their peers at school.

Already, districts that have divided those students have seen some students need more help than they anticipated.

In an attempt to avoid over-burdening district teachers, Niles Community Schools in southwest Michigan turned to outside providers to work with the 20% of its students who opted for fully virtual learning this year. While they were formally assigned a Niles teacher, students only interacted with the teachers employed by the outside companies.

Superintendent Dan Applegate says some fully virtual students had trouble staying on track. The district made some changes, such as assigning mentors to older students who were struggling to stay motivated. Students who weren’t logging in or doing work were encouraged to return to the classroom.

“Next year, we’ve got a better handle on all that,” Applegate says.

This fall, classroom teachers will interact with fully remote students more, fielding questions or reteaching lessons as needed. Applegate intends to use some of the new federal stimulus money to help pay for that additional instruction time.

Meanwhile, some school districts are launching more permanent online schools, or plan to house their fully virtual students at alternative schools. In Ohio, a school district in suburban Toledo plans to continue running its fully virtual option through an “alternative learning academy” that uses an online curriculum from an outside provider. Officials say they will improve the experience with Advanced Placement and honors courses, and will require students to attend regular meetings with their teachers.

Still, there are many external factors that school leaders say are complicating their ability to plan for what kind of instruction they’ll offer this fall.

Some are waiting to see if the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention drops its social distancing recommendation from six to three feet — which would allow many more students to come back into the building for in-person learning at a time — and whether quarantine times will be reduced or eliminated. This year, some districts have found that quarantines have required weeks of impromptu virtual lessons.

Other wild cards include exactly how many families will choose virtual learning, and whether states will continue to fund virtual learning at similar rates as students who are learning in-person. Many school leaders are now surveying families to gauge their interest in continued virtual learning and will do so throughout the summer.

Daniela Simic, the assistant superintendent of curriculum and instruction in Hillsborough County, Florida, said it could take until August for the district to know exactly how many families want to continue with virtual learning.

Right now, around 40% of students are learning virtually, but a lot could change in a few months. She expects as more people get vaccinated, more families will opt in. On top of that, she said, there could be new marching orders from the state. Last summer, Florida required districts to offer five days a week of in-person learning, with some exceptions.

“It’s going to be a little hectic,” she said. “It’s going to be similar to last year.”

The benefit of having gone through this already, she said, is they have curriculum and training for teachers ready — regardless of how many students learn online.

“We’re prepared to go into action and change our plans if need be,” she said. “We’ve gotten good at shifting our plans with very little notice.”

This article was originally posted on For some kids, remote learning will continue this fall. Can schools make it better?