I asked my daughter if she’d read Dickens. She asked me if I had read Trevor Noah’s memoir.

My children understand what great literature is. Libraries and reading lists are still catching up.

I grew up in a rural town in South Carolina, and I always had required summer reading. I took English courses taught by instructors with names that started with Doctor, as in Dr. Ferguson. I sat for the AP English test.

My reading lists included Mark Twain’s “Huckleberry Finn,” Faulkner’s “The Sound and the Fury,” Ernest Hemingway’s “The Old Man and the Sea,” and Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird.” There were Shakespeare plays thrown in, poetry by T.S. Eliot, and some short stories by Flannery O’Connor.

I walked away feeling well prepared to have absorbing discussions about literature in college courses or, even better, at cocktail parties. I had analyzed the terms and tones of the greatest authors in the world.

It wasn’t until I had children of my own that I realized I had been misled. When my daughter brought home her syllabus for ninth grade English, I saw that she was learning all the key aspects of grammar and writing, but the reading list had holes in it. Not to mention, many of the books were contemporary.

I would ask, “Are you going to read any Dickens this year?”

“I don’t know,” she’d reply.

Occasionally, I would see her reading a book with a familiar cover, but that rarity only seemed to highlight what wasn’t being read.

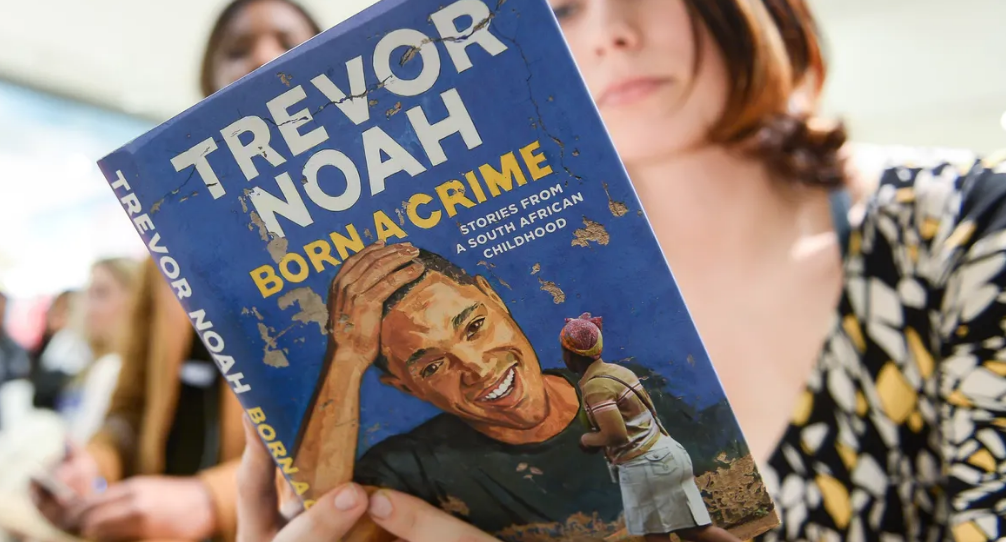

At some point, she brought home Trevor Noah’s “Born a Crime.” Months after reading it, she would recite a relatable coming-of-age anecdote about Noah or share an atrocity of apartheid he had lived through. She asked if I had read it, and when I confirmed I had not, she insisted I should.

This got me thinking. A contemporary book had made a great impact on my daughter, but I had never thought of modern pieces as great literature. Maybe a work didn’t have to be over 50 years old to be a classic; maybe a work just needed to resonate.

Around the same time, my local library was holding a quarterly advisory board meeting. I had been on the board for several years, and as such, I prided myself in getting to know the library’s inner workings.

At this particular meeting, we were being debriefed by the staff on the diversity of our current collection. We live in a university town, surrounded by multiple medical centers and industries involved in research and innovation. We all assumed that we would pass an audit on diversity with flying colors.

But while we had made major strides, the fact remained that a baby raccoon had more of a chance of seeing itself in a children’s book than a BIPOC child would. I’ll never forget the graphic of kids looking in a mirror, seeing themselves reflected as a symbol for the number of books that would speak to a particular child’s experience (or even existence). The graphic demonstrated that the white child had plenty of titles and the youngsters of the animal kingdom had a lot, too. But for anyone else, it was slim pickings.

This diversity gap again pointed to the flaw in my belief that great works have to age like wine. Older works will represent the point of view of those allowed to tell their story at the time. But there are so many stories that were left out.

I began to think about what I’d missed. I hadn’t really seen myself in the novels that I read growing up. My family came through Ellis Island. My mother was the first in her family to go to college. I had olive skin, and peers often asked where I was born. When I answered Philadelphia, the kids would ask what country that was in. What classic piece of literature did I read in my formative years that reflected anything close to what I was experiencing?

I didn’t question whether the books I read in school were giving me anything in return other than the honor of having read them. I checked them off my list and then conquered another one. What if I had read a list as diverse as my daughter’s? What if I kept thinking about a book for days to years after reading it because it made me think? Not about metaphors or themes but about how it reflected another human experience, one not shared as often?

Yes, many of the books that I read in school were excellent examples of writing. But they weren’t the only excellent examples of writing. They were the ones that were deemed great, whether it was because the authors were male or white or the works had been around for so long.

I’m not advocating taking books off the shelf because of who wrote them or because they make us uncomfortable about our past. At a time when the debate is raging about what books should be in libraries or schools, I’m advocating that the books included in these buildings and on reading lists need to reflect all of us. And all of our experiences.

My daughter graduated high school this spring. She’s going to college ready to discuss the books she read. Not because she got through them, rather because they got through to her. She read works that were old and contemporary. By authors that are considered classic and those that are modern but already respected. Books filled with stories about people like her and others about people that she was lucky enough to get to know. Her reading lists throughout high school model what we all should be reading, not just in class but in life. Great literature may even be the novel that was written just last year.

The good news is my daughter already knows this. Turns out that I was the one with a narrow view of what the best of literature ought to be, and my high schooler opened my eyes to what I was missing. I’ll admit that she’s more well-read than I am. That’s OK. For now.

This article was originally posted on I asked my daughter if she’d read Dickens. She asked me if I had read Trevor Noah’s memoir.