Inside the nationwide sprint to build big new programs to catch students up

Oklahoma education officials came up with an ambitious plan to help students who struggled during the pandemic: build a 500-person math tutoring corps.

The goal is to have 250 tutors in place by January. But first, the state has to find them.

Already, they’ve changed their recruiting approach. After assuming most of the tutors would be college students, university presidents warned officials to expect only “about half of the tutors we were initially seeking,” said Joy Hofmeister, the state’s schools chief. Now, the state is also targeting teachers, retired educators, and some 30,000 others with teaching licenses — and plans to pay teachers who tutor $50 an hour.

Hofmeister hopes that will be enough to draw in even tired teachers, who they now need to make the program work. “We need to really honor the fact that they are currently moving heaven and earth for the kids in their classrooms, and this is above and beyond that,” she said.

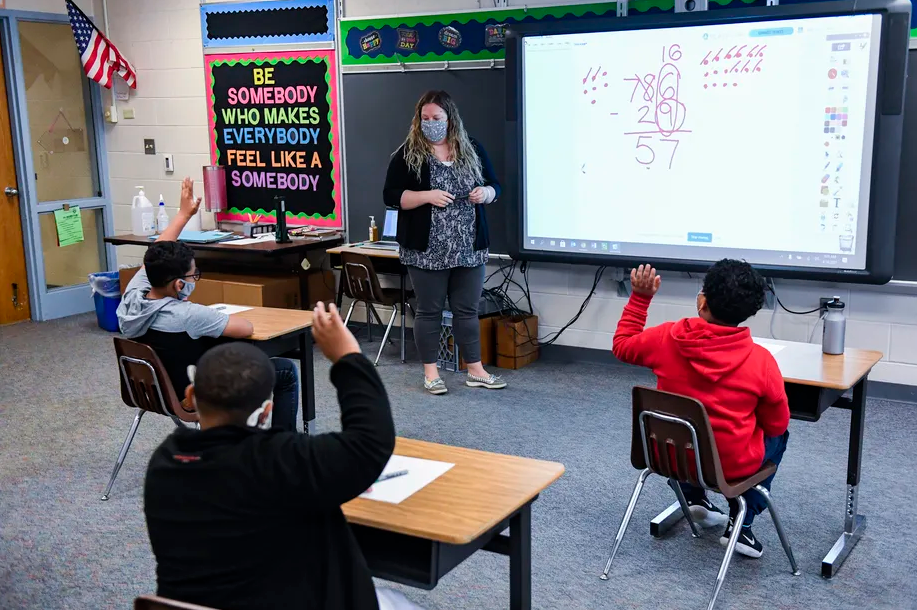

Several states and many school districts are launching massive tutoring programs of their own with coronavirus relief money. The idea is not just sporadic after-school homework help, but tutors working with small groups of students, during the school day, two or three times a week — the kind of “high dosage” tutoring that’s considered one of the most promising strategies for catching students up.

But finding tutors has been harder than many expected, as a national labor shortage and educator exhaustion complicate recruiting and hiring. As a result, states and districts are getting creative — and paying much more than they typically would. Still, some expect it won’t be until next year or later that they’ll fill their tutoring slots.

“The biggest pain point for districts will be the sourcing of talent — it will be a challenge to find qualified tutors,” said Alan Safran, the CEO of Saga Education, which is running tutoring programs in the Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Providence, Rhode Island school districts and is advising others. “It just takes time to roll a good idea at the federal level into execution at the local.”

New Mexico, for example, is recruiting 500 “educator fellows” to work alongside teachers and provide small-group tutoring. The goal is to have half in place by January. Arkansas wants to recruit 500 math and reading tutors for its corps by June, with half ready to go by December.

Chicago is recruiting 850 math and reading tutors over the next two years, with the goal of having 650 in place this school year. In the Denver area, a private philanthropy, Gary Community Ventures, is looking to hire 500 reading and math tutors to work in the city and nearby suburban schools, and has recruited 300 so far.

Those big numbers represent the hands-on help schools think students need right now. But few imagined an environment as tough to find those tutors as the one they’re facing.

“It’s hard when places like McDonald’s are paying $20 an hour and paying tuition for employees,” said Whitney Oakley, the deputy superintendent of Guilford County schools in North Carolina, which is looking to hire 500 tutors, mostly for math. The district has 240 employed so far, with 50 more in the hiring pipeline. “We’re competing with everyone else who’s trying to hire people right now.”

In the Dallas Independent School District, too, competition from retail stores and restaurants has made recruiting tutors “a lot more challenging than we anticipated,” said Susana Cordova, the district’s deputy superintendent.

Over the next three years, her district plans to bring in 1,800 tutors, mostly through contracts with outside providers, though it’s looking to hire 105 tutors itself this fall. Demand may grow after Texas passed a law requiring more students to receive tutoring.

“The most important thing that we are really trying to be thoughtful about is doing it right, as opposed to doing it fast,” Cordova said.

Many programs are putting tutors through fairly rigorous training. Arkansas is requiring tutors to spend six hours learning about the science of reading and another six studying how to teach math. Others are asking tutors to learn how to devise a tutoring lesson, test students for skills gaps, and provide social and emotional support.

To attract quality applicants, several programs are offering higher-than-usual pay and other perks. The Chicago, Dallas, and Denver area initiatives are paying college-age or adult tutors at least $20 an hour. Oklahoma is paying college students $25 an hour. Some are giving high school or college students course credit. And New Mexico is offering educator fellows a $4,000 stipend toward any degree in education, in the hopes of converting some into teachers or other school staff.

Roosevelt University, which is helping the Chicago district with its early literacy tutoring, is providing child care and travel stipends to tutors who need them, after hearing those costs were barriers for prospective tutors from the communities where schools most need extra support.

“That’s really a result of thinking about the types of candidates we want,” said Allison Slade, who is overseeing Roosevelt’s tutoring program. “We have a corps that is highly Latinx and African American, so that the students are seeing people that look like them and they can identify with.”

Many efforts are offering teachers extra money to tutor during their prep periods or before or after school, but they’ve found teachers are often too exhausted to take on more work. In Metro Nashville schools, teacher recruitment has been tough, in part because educators have had to use their planning periods to step in for colleagues in quarantine.

“We’ve heard that there is a lot of interest,” said Keri Randolph, who’s overseeing the tutoring initiative for the district. “But there’s a lot of: ‘I just can’t do it this semester, there is too much happening.’”

Recruitment efforts are tapping other talent pools, too. Dallas reached out to an unemployment agency, and Guilford County is working with a historically Black university known for engineering to find grad students willing to help students with the biggest math needs. Metro Nashville targeted businesses with community service programs and has on-campus college “ambassadors” promoting the tutoring roles.

Some states and districts are even turning to high schoolers. But matching tutor and student schedules during the school day is challenging, especially because schools don’t want to pull students from core classes.

In Guilford County, high school counselors pored over a list of students who’d done well in math. They found dozens willing to tutor middle schoolers, and they’ve already begun, mostly virtually. The district hasn’t yet “ironed out” how to make those matches work in person, Oakley said.

Schools do see some benefits to virtual tutoring. It cuts down on travel time and transportation barriers, which was appealing to Oklahoma officials worried about recruiting for rural areas. Metro Nashville schools are also using virtual tutors, allowing the district to recruit mostly volunteers who see the work as community service.

But after students struggled to learn virtually for the last year and a half, many states and districts want tutoring to happen in person.

“We’re very much prioritizing in-person,” said Gwen Perea Warniment, the deputy education secretary who is overseeing New Mexico’s tutoring efforts. “We see that it’s pretty crucial right now.”

In Arkansas, Missy Walley and her team have been criss-crossing the state to visit every teacher prep program, in person. They’ve noticed that when they go into classrooms and explain the need, more college students show up to tutor training.

Walley is hopeful she can get to her goal of 250 tutors by the end of the year. What keeps her motivated is knowing how much schools need their help — and the evidence is on her phone.

“They’re highly interested,” she said. “They’re to the point that they’re calling us and saying: ‘OK, we’re ready to get tutors.’”

This article was originally posted on Inside the nationwide sprint to build big new programs to catch students up