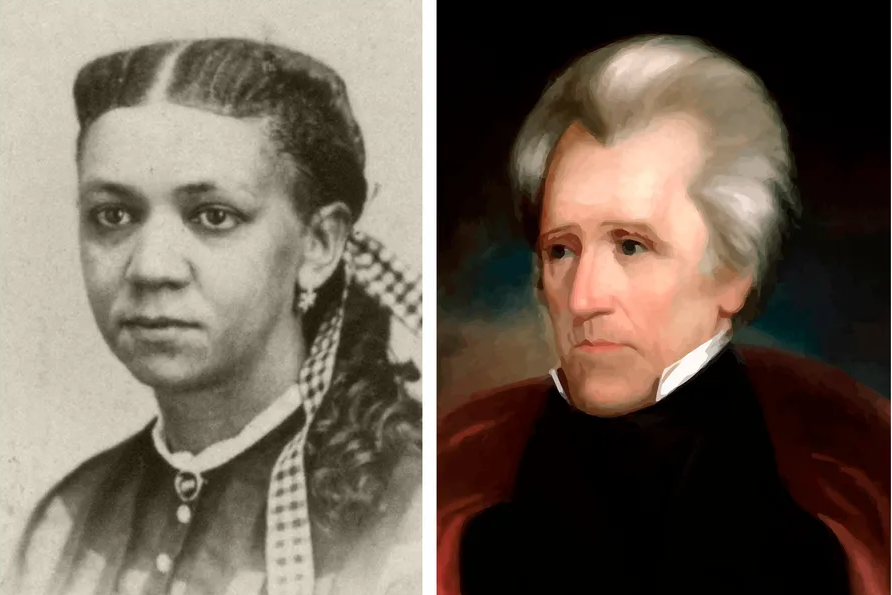

Philadelphia school renamed for Fanny Jackson Coppin, former enslaved woman and educator

The elementary school had been named for Andrew Jackson, a slave owner and the country’s seventh president.

Many memorials, statues and buildings honoring past Confederate leaders and others who promoted or profited from slavery and racism, have either been toppled or renamed across the country amid protests against racial inequality and injustice over the last year.

Four years ago, a group of community organizers in Philadelphia, led by Brian Kall, argued that Andrew Jackson Elementary School should not bear the name of the seventh U.S. president. Though he was not a Confederate and died before the Civil War, Jackson owned nearly a hundred enslaved Black people by the time he got in office. The school, which opened in 1924, is located at 1213 S. 12th St. and sits in a racially diverse area in South Philadelphia.

“Andrew Jackson has virtually no connection to Philadelphia, having only come to the city as a representative of Tennessee when Philadelphia was the nation’s capital,” Kall said in his petition for the name change. “There is no reason to continue honoring the legacy of this man when there are Philadelphians who more greatly deserve the recognition. He was a slave owner, and led multiple campaigns to purge America of its native inhabitants, both as a military leader and as president.”

Last week, the city’s Board of Education agreed and voted unanimously to rename the school after Fanny Jackson Coppin, a former enslaved woman turned educator with Philadelphia ties. The new name goes into effect Thursday.

“The School District of Philadelphia recognizes that school names are an important part of students’ learning environments and should cultivate a sense of pride in the history and traditions, to ensure that all students, staff, and families feel respected, seen, and heard,” the district said in a statement.

According to the district, the renaming came after several months of engagement with the Jackson Elementary School community, which included a series of surveys, focus groups and meetings. During the spring, more than 1,100 school families and community members responded to a survey seeking input on a final name. A total of four possible names were up for consideration, with Coppin receiving the most support. The other three names included: former Philadelphia Inquirer editor Acel Moore; civil rights leader Barbara Rose Johns; and Black abolitionist William Still.

Naming new schools or renaming existing schools begins with a formal, five-phase process that includes a review, community engagement, a review by the superintendent and finally, approval by the board, according to the district.

Born into slavery in Washington, D.C. in 1837, Coppin eventually gained her freedom as a child and received some schooling while working as a domestic worker. As a teenager, she supported herself after relocating to Newport, Rhode Island, and graduated from the Rhode Island State Normal School before attending Oberlin College in Ohio where she organized evening classes to teach freedmen. In 1865, she became the second Black woman to graduate from the college.

After her graduation from Oberlin, Coppin came to Philadelphia to work at the Institute for Colored Youth, a Quaker school where she eventually became head principal, a role she would hold until her retirement in 1902. The school would eventually move from Philadelphia to outside the city limits in Delaware County and be renamed Cheyney University, becoming the first higher education institution in the U.S. for Black people.

After her retirement, Coppin became a missionary with the African Methodist Episcopal Church and served in England and South Africa. Her autobiography, Reminiscences of School Life, a collection of essays on her views of education and missionary work, was published in 1913 shortly before her death at the age of 76.

“Fanny Jackson Coppin dedicated her life to education, doing whatever was necessary to ensure that people from underserved communities and women had access to a high quality education,” said Jackson Elementary School Principal Kelly Espinosa. “She understood that education is the greatest tool in building a positive and productive life and this is a message that still rings true today.”

“The very principles that she fought to uphold nearly 200 years ago are ones that we instill in our students today and will continue to be what helps drive positive and lasting impact for generations to come,” Espinosa said. “This name is about recognizing the contributions of an educator whose work isn’t widely known, but it’s also about showing our students the impact they can have on the lives of others.”

Coppin is also the namesake of Coppin State University, an historically Black college in Baltimore, which was founded in 1900.

“As the fight for fairness and equality continues, my hope is that plans for renaming and other methods aimed to cure the many racial issues that we face are also accompanied by the work and resources necessary to move us forward, in a meaningful way,” Anthony Jenkins, president of Coppin State University, told Chalkbeat.

Linn Washington, a professor in the Klein College of Media and Communication at Temple University, called the renaming appropriate and educational.

“Having a school named after this widely respected educator is itself a ‘teachable moment’ that opens insights into inspiring historic accomplishments that are too often ignored,” he said.

Angela Crawford, a teacher at Martin Luther King High School, said “Fanny Jackson Coppin is the epitome of Black women teacher love. Her legacy is one that should be amplified.”

This article was originally posted on Philadelphia school renamed for Fanny Jackson Coppin, former enslaved woman and educator