This award-winning Bronx math teacher developed a curriculum on gerrymandering

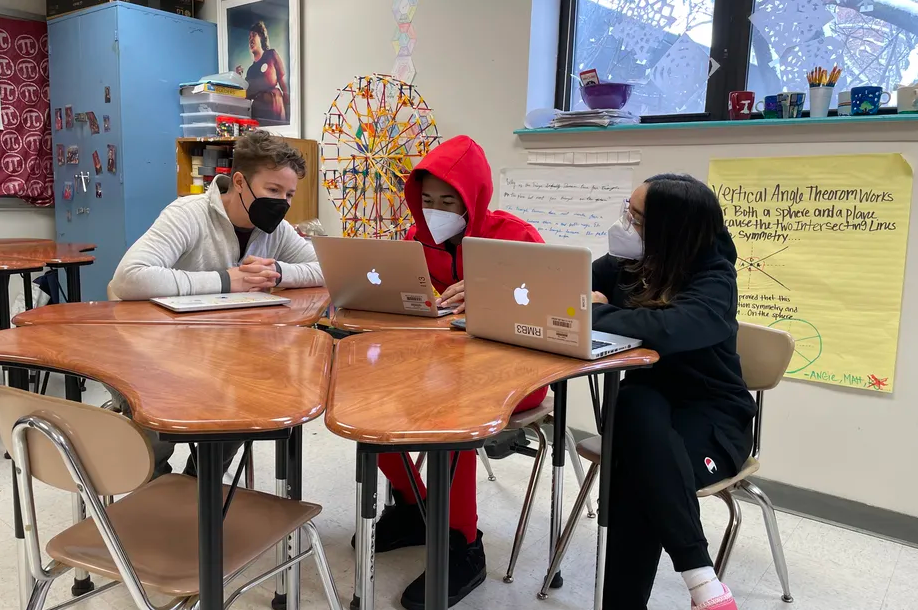

In certain high school educator circles in New York City and beyond, Kate Belin is a rock star.

The veteran math teacher has won numerous accolades for her work with students and her mentorship of teachers, including most recently the 2021 Math for America (MƒA) Muller Award for Professional Influence in Education.

Belin (who uses they/she pronouns) has not only spent her entire 17-year teaching career at the Bronx’s Fannie Lou Hamer Freedom High School, but they also have taught at City College of New York, Bard College, and the Bard Prison Initiative. In addition, she is a national teacher trainer for the Algebra Project and is working to amplify teacher voices.

Belin has developed a curriculum that includes a course on the ever-relevant topic of gerrymandering — diving into how boundaries of electoral districts are drawn to favor certain political interests — that is used at Fannie Lou and other New York City “consortium” schools. Those schools, which Chancellor David Banks has repeatedly said he’d like to replicate, focus more on hands-on learning and performance-based assessments than Regents exams. (To graduate, students at consortium schools only have to pass the English Regents while having other projects or portfolios to complete to show their mastery of skills.)

“Without a doubt, my greatest professional impact comes from the work I do with my students at Fannie Lou,” Belin said. “But I do have an agenda. I want to see a national shift in how we teach math, what math is, and who has access to it. Everyone should have access to high-quality math instruction. And math should be understood as something that is relevant, intuitive, all around us, and not as something that is accessible only to some.”

Belin spoke recently with Chalkbeat about the mathematics of gerrymandering, how she knew she wanted to work at Fannie Lou, and why she sees teaching as inherently political. .

Was there a moment when you decided to become a teacher?

I was a math major at Bard College. It was 2004, my senior year, and I had spent four years falling in love with math but ignoring the question of what I was going to do with it. During that year, Bard announced they would be starting a Master of Arts in Teaching program the following year. It would be a 12-month intensive program, and their vision was that pre-service teachers would be scholars of both education and the discipline they taught. I knew pretty quickly that I wanted to apply.

I learned in college that mathematics was about creativity, patterns, problem-solving, and many more things that aren’t necessarily taught in K-12 school. There are so many students who hate mathematics because standardized testing shows them that it is about memorization, rote procedures, and getting a correct answer. The master’s program at Bard College gave me hope that it was possible to bring more real mathematics into schools and that more students might fall in love with it, too.

But looking back even further, my Aunt Mary was a high school history teacher, and I’d probably known that I wanted to be a teacher subconsciously for much longer, even though I went to college with dreams of being a photographer.

I saw that you’ve led MƒA workshops on developing project-based curriculum in geometry, functions, and gerrymandering. How did you start incorporating gerrymandering into your lessons?

We kicked off the new semester in February with gerrymandering.

In 2017, the Metric Geometry and Gerrymandering Group, or MGGG, was formed at Tufts University and led by Moon Duchin. That summer, they offered a workshop about the mathematics of gerrymandering that was open to the public. Interest was so overwhelming that they ended up having satellite conferences throughout the country later that year. There was an option to apply for an educator track following the conference, and Math for America supported the resources for me and a few other teachers to attend.

The conference and materials were so wonderful that Math for America ended up bringing a professor from MGGG to teach a mini-course at [its conference] the following year. Since then, there has been a growing group of teachers at MƒA continuing to lead professional development workshops for other teachers and using the materials in our own classrooms.

Why is it so important to teach about gerrymandering? This feels especially relevant in terms of what’s happening in NY right now!

I’m on a two-year curricular loop, so this is the third time I’ve taught it, and in each of the years 2018, 2020, and now 2022, it has felt “especially relevant.” The first time I taught gerrymandering was 2018. There was huge interest coming off the 2016 presidential election and dealing with the Republican gerrymanders. This was the year [2018] that the Democrats “took back the House,” and AOC along with a number of other progressive Democrats won. Then in 2020, it was especially relevant because of the Census. And now in 2022, we are seeing the new redistricting maps and anticipating the 2022 midterm elections. It absolutely is an especially relevant topic and will likely continue to be.

It’s also just a pretty cool coincidence that I always end up teaching it in the spring of every even-numbered year, and all 435 seats are always up for reelection those same years.

At Fannie Lou, how do you get to know your students?

Prioritizing it. At the beginning of the year, I try to design activities that explicitly help us get to know each other. I try to make these activities as fun and interactive as possible. We also have many structures built into Fannie Lou that make this possible. For example, we loop with our students for two years. So the same team of teachers will work with the same cohort of students for both 11th and 12th grades.

In addition to teaching math, I am also an advisor to a group of about 20 students. Advisory meets daily and is also part of the same two-year loop.

What are you doing differently this year after the prolonged stretch of remote learning and social isolation?

This connects completely to the [previous] question. I love my advisory this year more than any other, but I think that is because it was what we missed the most in remote learning. We spent at least the first month, if not more, playing games, bonding, learning each other’s names. I was more explicit about this with the students this year.

I’ve also noticed that students were much more resistant to using computers in class. It makes total sense now, but I was surprised by how serious some students were about wanting to do activities with physical materials. During remote learning, I guess I had in my mind that much of the digital literacy that they learned would seamlessly transfer into the school year. But they wanted to be interacting through conversations or paper much more.

In the MƒA award announcement, you said: “This award also recognizes the work of the entire Fannie Lou community which has always understood that teaching is political.” It sounds like you have an inspiring school community. Can you tell us more about how your school has shaped your work and about how teaching is political?

When I visited the school in 2005, I walked in and instantly knew that this place felt great. When I met the (former) principal Nancy Mann, I knew I wanted to work for her. Rather than seeing myself as a math teacher, my job is teaching students to want to know math.

The structures that I mentioned above (advisory, block scheduling, and much more) are themselves political. “School,” or what we think of as school in the traditional sense, has failed (intentionally) so many of our students. Schools should be intentionally designed from the ground up to meet the needs of the community it serves. In “Teaching to Transgress,” bell hooks talks about how education is freedom. Schools are not politically neutral and are, in fact, deeply rooted in the antiracist struggle.

You also talked about the importance of collaboration with your students, working together and mobilizing youth for positive change. Do you have any anecdotes about specific projects your students have worked on that you’re particularly proud of?

There have been a ton of initiatives led by students at our school. In my first year here, NYC schools were doing Principal for a Day, and we got Mitchell Modell (CEO of a sporting goods chain). After talking with the students, he decided that he wanted to work with the students over a longer period of time. Together, they decided that a class at Fannie Lou would spend the semester designing a boot.

The annual Peace Block Party is another great example. In 2010, after a spring break where many of our students lost friends and loved ones due to violence, the students wanted to create an event that promoted peace. The event has grown bigger each year, it is now an institution of the school each spring, and it has even continued virtually during the pandemic.

This Q&A is celebrating your accomplishments, and I don’t want to detract from that, but if you are open to answering this, I’m curious to hear how your school community is doing after the stabbing incident in October. This year has been so hard on many kids and educators, and we’ve seen incidents spiking in schools across the city. How do you in your role as a math teacher support your students who are going through so much?

I’d prefer not to discuss the stabbing.

Being away from our community in the physical school building had tremendous impacts; that’s why it is important that the structures at our school, such as advisory, looping, using essential questions, and writing across the curriculum assist us in building relationships with each other and putting students ideas at the front of their learning in all content areas.

What’s the best advice you’ve received or given about teaching?

A lot of it has been really practical, like don’t keep your house keys attached to your school keys because you’ll end up locked out of your house when you lose your keys at school (and you WILL lose your school keys). Call your principal if you get arrested. Stuff like that.

But then there’s the deeper stuff – have a sense of humor, demand academic success, believe in the abilities of your students. I keep in mind this quote from Maya Angelou: “People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

This article was originally posted on This award-winning Bronx math teacher developed a curriculum on gerrymandering