Speakers urge school board to reopen more Philadelphia schools for more students

Starkly describing young people who are bored, depressed, falling behind, and more vulnerable to violence, scores of speakers urged the Philadelphia Board of Education at a public hearing Thursday to open schools as quickly and as completely as possible.

“All kids need to be back. Their mental health is taking a hit,” said parent Lindsey Birckhead. Marshall Fong, a parent at Eliza B. Kirkbride, a K-8 school in South Philadelphia, said children who have not been in school in person this year have been “forced into a disadvantage that will follow them for the rest of their lives.”

The meeting was in stark contrast to July, when more than one hundred parents, teachers and students flooded the board meeting to declare that opening schools put people’s lives at risk. The outpouring led Superintendent William Hite to abandon plans to open the school year in September with a hybrid model starting with the earliest grades.

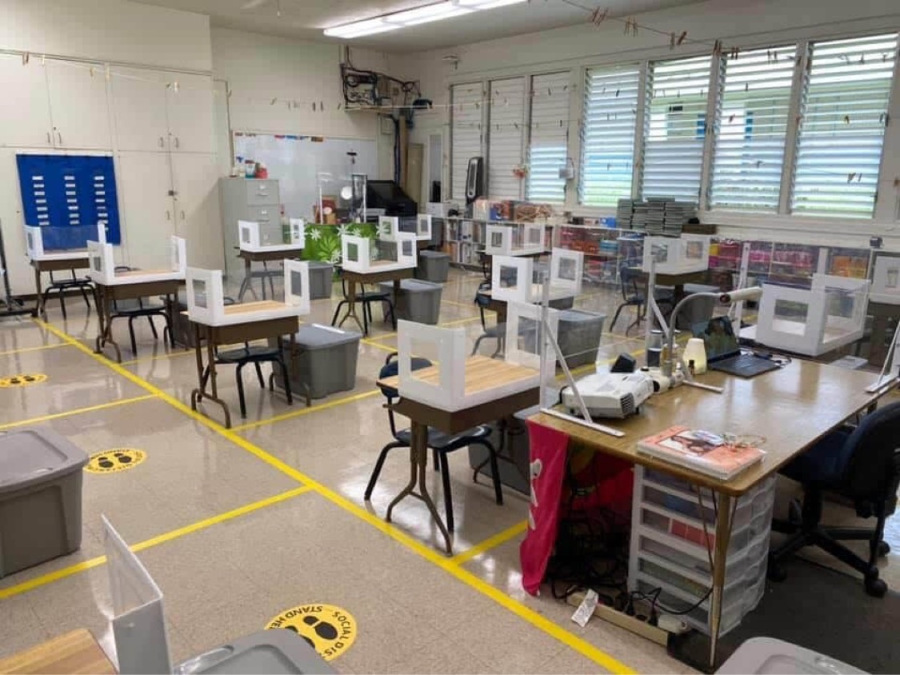

School buildings finally opened this month for kindergarten through second grade, the district’s fourth attempt after prolonged opposition from the teachers union, primarily over building safety.

This time, people came armed with data from studies from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the experiences of other cities and Philadelphia private schools, which opened in the fall, arguing that circumstances have changed and that the dire toll of full-time virtual schooling is becoming more apparent.

“The moment the data made closing schools the only course of action, we supported it,” said Thomas Novak, a father of four students. “We are neither for opening schools at all costs, nor are we for keeping schools closed at all costs. But now it can be said that in- person schooling provides only a small health risk.”

Students of all ages also made heartfelt pleas.

“I’ve been slowly losing my motivation,” said Mason Seder, a student at McCall Elementary School. “I barely get any social interaction…that’s something I really miss.”

Abigail Gorman, a student at Girard Academic Music Program, or GAMP, also said she was suffering and raised questions of fairness and equity.

“Kids in private schools are in school in person, why are public school kids still virtual?” she asked. “It’s tough for me to make friends. Trying to get to know someone from behind a screen is not the same.”

Public speakers who were calling for a larger reopening were undeterred by the temporary closure of Mayfair Elementary, which shut down Thursday because of positive COVID-19 cases. But many did call for more transparency, echoing the teachers union’s demand for the district to create a dashboard that details where and when positive cases occur.

A few speakers urged caution. Zoe Rooney, both a teacher and parent, cited a recent death due to the coronavirus in one of her school communities. “It’s not over. Nobody can say what acceptable level of risk is. For many COVID is devastatingly real,” she said.

The hearing, which lasted five hours and had 133 registered speakers, is one of two the city charter requires the board to hold annually as it considers spending priorities. Schools recently received their individual budgets and the board must adopt its own $3.2 billion spending plan by the end of May. It will outline its general “lump sum” budget at its meeting March 25.

More than a dozen principals and other administrators also made a coordinated pitch that all schools be allotted four key positions that now depend on a school’s size, eligibility for federal funds, and capacity to raise funds from parents.

The positions – assistant principal, full-time literacy and math teacher coaches, and a special education compliance manager – are not automatically budgeted for schools.

But the principals, in a campaign coordinated by their union, the Commonwealth Association of School Administrators, known as CASA, argued that all schools need them, especially now.

“We have to allocate resources equitably without employing a robbing Peter to pay Paul mentality,” said CASA President Robin Cooper.

Principal after principal repeated that theme, reminding board members that their own “goals and guardrails” initiative has highlighted the system’s stark inequities and requires bold action to address.

“This is a year like no other,” said Kiana Thompson, principal at the Academy at Palumbo. “When students return they need support socially and academically. It’s unimaginable we see cuts at this time.”

The principals are supported by parents and advocates through the Campaign for Equitable Resources. That campaign also wants all schools to have a climate manager, which is a person who helps build positive school culture.

“This is what we demand, this is equity, this is right. We can’t afford not to do that,” said Phillip DeLuca, principal of Gompers Elementary School, who also advocated for smaller class sizes. “It’s time to stop saying things like this will never happen.”

Overbrook High School Principal Kahlila Lee, in advocating for more staffers, noted and named three students, who have been shot since October.

“We need more counselors…[but also] art, music, drama… Yet we continue to use the same budget structure we’ve been using for decades without standing firmly together to make sure it is equitable,” she said.

The district is due for more than $1.2 billion in federal pandemic-relief funding from the American Rescue Plan over the next few years, but that is one-time money. Policymakers discourage spending it on permanent positions that could then be cut, which is what happened in Philadelphia after the 2008 recession.

Then, the district lost more than $250 million when Harrisburg used the federal money to replace state aid and then never replenished the state subsidy. This forced cuts from which the district has never recovered, including some of the positions that the principals are now demanding.

This federal rescue package forbids states from using the money to replace its own investment.

Board members said they appreciated the challenges and new ideas the speakers raised, especially from students.

Vihaan Kaushik, a third grader at Meredith Elementary School, noted that the district has stopped using Google Meet, which students used for social interaction with parental approval and were now denied. Central High School student Keyanah Campbell said the district should allow students to use electronic texts from now on instead of carrying heavy books around. Board members said they would explore both issues.

“Budgets provide insight to an organization’s values, and we will make difficult decisions as we work to align resources with the goals and guardrails and wrestle with the meaning of equity,” said board President Joyce Wilkerson.

Several board members agreed that schools should fully open as soon as possible. “Hospitals have been overwhelmed by mental health admissions because of kids being socially isolated for so long,” said Maria McColgan, a pediatrician who specializes in child abuse. “We’ve seen increased child abuse rates; we’re even seeing more cases that reach the level of torture. And we do not use that word lightly.”

Wilkerson made a plea that the district’s parents, unions and supporters join in advocating for more funding from the state. Philadelphia is the only district in Pennsylvania that has no control over its revenue, depending entirely on what the city, state, and federal governments choose to give it. Although it controls how the money is spent, it cannot raise taxes on its own.

Pennsylvania’s system “cheats our children of fair and equitable funding,” Wilkerson said. “We urge the entire school community to actively lobby to fix the initiatives spoken about today.”

This article was originally posted on Speakers urge school board to reopen more Philadelphia schools for more students